Research shows that the human condition can be the defensive investor’s worst enemy.

Graham admonished investors not to sell securities, especially on the downside, if their fundamentals remain sound.

A “Ben Graham defensive investor” should find much to like in the RAFI™ Fundamental Index™ strategy.

Are you a value investor? Not everyone is. But if you are, that is, you believe in buying companies with good fundamentals at cheap prices and selling companies (promising or not) that have ridden momentum to the point of overvaluation, you are following in the footsteps of one of the most insightful and forward-thinking investors of all time, the “father of modern security analysis,” Benjamin Graham—and by extension, those of Warren Buffett, who claimed of Graham that “[m]ore than any other man except my father, he influenced by life” (Graham, 2006, p. ix). No light testament.

One might think that Graham’s outspoken preference for value investing would pit him against the early proponents of index investing; it turns out, however, that his pragmatic perspective on investing did exactly the opposite. Although Graham did not live to see the explosion of index funds that originated with John Bogle at Vanguard in 1975, indications are that he would have found much about them to like, as Jason Zwieg (2015) pointed out in his article “Would Benjamin Graham Have Hated Index Funds?” In a June 1974 speech, Graham explained:

More and more institutions are likely to realize that they cannot expect better than market-average results from their equity portfolios unless they have the advantage of better-than-average financial and security analysis. Logically this should move some of the institutions toward accepting the S&P 500 results as the norm for expectable performance. In turn this might lead to using the S&P 500…as [an] actual portfolio….

Graham expounded further on the subject in a brokerage firm’s client Q&A in the fall of 1976, stating that the average institutional client should be content with the DJIA results, or the equivalent, and that “they should require approximately such results over, say, a moving five-year average period as a condition for paying standard management fees to advisers and the like” (Zwieg, 2015).

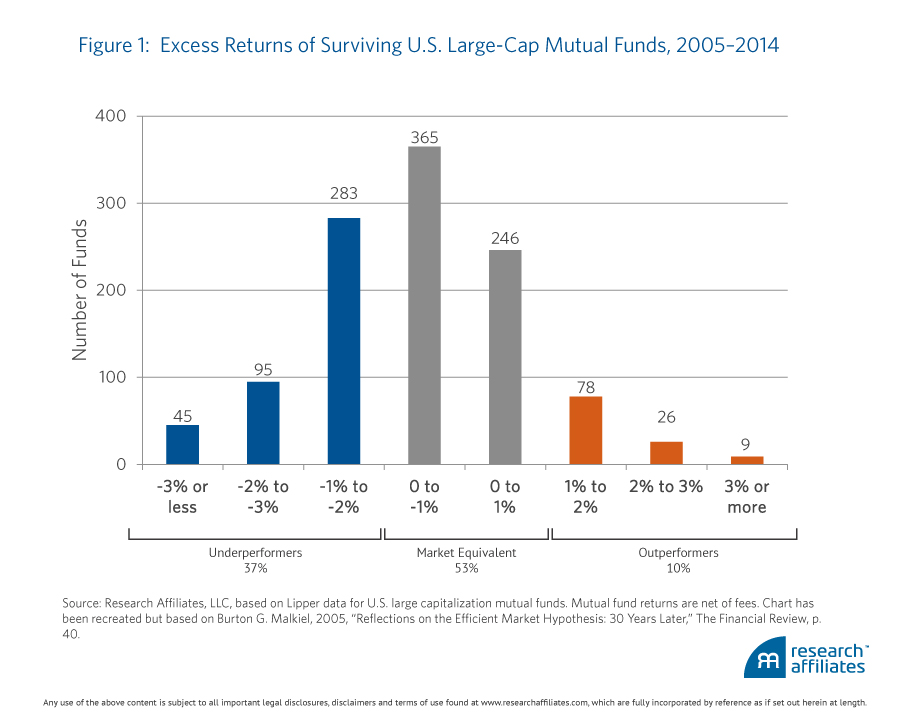

So not only did Graham subscribe to the idea that an index fund’s market return should be viewed as acceptable for the average investor, but that in order to earn their standard fees, active managers have a duty to match or improve on the market return over relatively long (at least by today’s standards) investment horizons. Few managers are able to achieve this. Figure 1 shows that from 2005 to 2014, of the 1,147 surviving U.S. large-cap mutual funds, only 10% outpaced the market by 1% or more, after fees. Almost four times as many lagged the market by 1% or more. It’s a safe bet that the funds that failed would not improve this bleak picture.

Given that a market-cap-weighted index fund offered investors a low-cost, market-return alternative to active equity management beginning in the mid-1970s, investors received yet another game-changing boost, roughly 30 years later, with the introduction of the RAFI Fundamental Index.

The RAFI Fundamental Index severs the link between stock price and portfolio weight, weighting index constituents by sales, cash flow, dividends, and book value (i.e., a company’s metrics of fundamental value). Such a structure retains the positive attributes of passive investing—low turnover and low trading costs, high capacity, and broad economic representation—while delivering excess returns versus a core cap-weighted market portfolio. As of July 31, 2015, the broadest FTSE RAFI indices have exceeded the performance of corresponding cap-weighted indices since their November 2005 inception, even though value indices have been savaged. The Developed Ex US 1000 Index posted a 10-year annualised return of 5.96% compared to the 5.50% return of MSCI EAFE Index, and the FTSE RAFI 1000 Index posted a 10-year annualised return of 9.04% compared to the S&P 500 Index return over the same period of 7.89%.

In his ground-breaking guide to investing, The Intelligent Investor, Graham makes a crucial distinction between a “defensive” investor and an “enterprising” investor. The defensive investor’s chief emphasis is on “the avoidance of serious mistakes or losses” with a secondary aim of “freedom from effort, annoyance, and the need for making frequent decisions.” These are common goals for passive investors and for patient value investors. In contrast, the enterprising (or active) investor is devoted to finding securities that are “both sound and more attractive than the average” and, over time, should be rewarded by earning a higher average return than the defensive, or passive investor. That said, Graham expressed “some doubt” this would always be the case, given the vagaries of market conditions (Graham, 2006, p. 6). Ample evidence suggests that most active investors can’t help themselves: they chase the popular and expensive issues, proving Graham’s doubts true over the long term.

Graham consistently stressed the importance of value investing with a focus on security selection supported by a firm’s financial strength, earnings, dividends, and assets. Preferring the objective to the subjective, he provided a set of rules for security selection decisions as a means to remove subjective factors that can mislead investors. Errors of judgment that can occur during the market’s heights of euphoria and troughs of despair, often a function of decision inputs unrelated to intrinsic value, are anathema to well-reasoned, thorough analysis that occurred prior to the market’s gyrations.

Investors who identify as a “Ben Graham defensive investor” and adhere to his belief in the long-term benefits of value investing will find much to like in the Fundamental Index strategy. The strategy applies a disciplined, quantitative approach to security selection, annually reweighting portfolio positions to align with each company’s fundamental value metrics. The effective result is to sell securities whose price, and therefore capitalisation, has increased over the year relative to its metrics, and to buy those securities that have had the opposite experience.

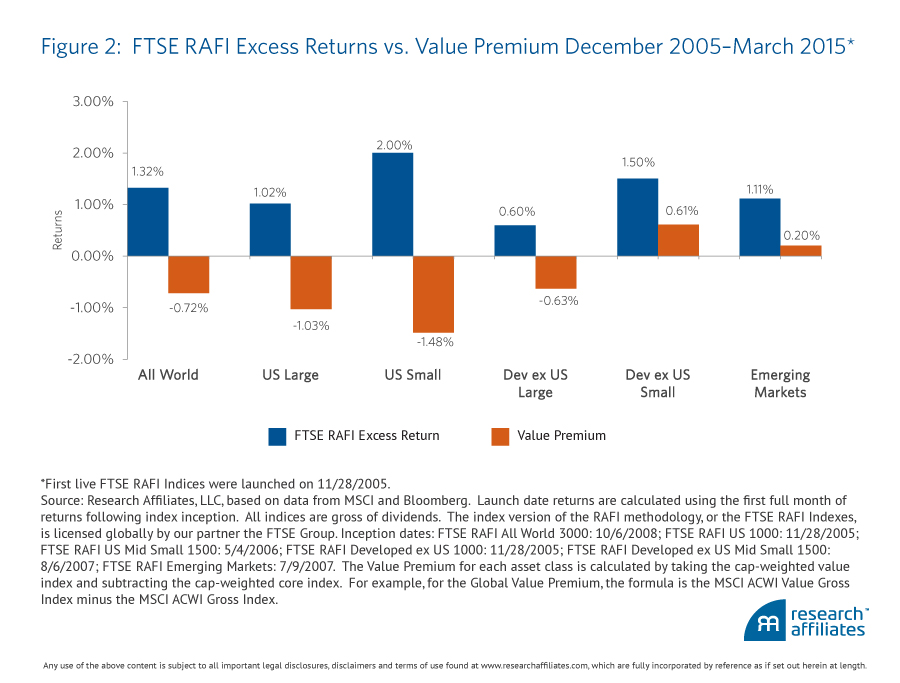

The reweighting mechanism of the RAFI Fundamental Index is not based on value per se, but the systematic rebalancing that contra-trades as price changes stray from (grow or shrink faster than) company fundamentals. The result is a dynamic exposure to value and size factors, ramping up exposure to these factors when they are most out of favour and lowering exposure in whatever the market favours most. Figure 2 compares the excess returns earned by the RAFI strategies over the last decade with the value premiums earned (or not) for the same strategies. The value premium lagged across most markets, while the RAFI strategies outperformed in each. Looking back 50 years, the respective Sharpe ratios of the cap-weighted portfolio and the fundamentals-weighted portfolio are 0.33 and 0.47,1 respectively, indicative of their relative performances.

If we accept Graham’s thesis that a value investing strategy will consistently deliver a premium over a market portfolio, which is a cap-weighted portfolio, and empirical research has documented the existence of a value premium over the last 86 years, albeit with the exception of the last decade,2 the obvious question is: Who are the investors willing to take the other side of the trade? After all, the net performance of all market participants—relative to the market—must cancel: for every outperformer there is an underperformer.

Hsu, Myers, and Whitby (2014) show that from 1991 to 2013 value managers did capture a premium versus the S&P 500 when measured by the buy-and-hold return. But the dollar-weighted return of the value managers tells a vastly different story. On average, over the 32-year study period, investors lost nearly 14% of the value strategy buy-and-hold return simply by embracing and shunning value managers at the wrong time. Holding any contrarian position, whether it is part of a dedicated value strategy or a component in a contra-traded rebalancing strategy, such as RAFI, is very difficult for many investors. These disheartened or fearful investors—possibly struggling with career risk or myopic loss aversion, or ultimately, just from the human condition—are often the other side of the trade. Courage and conviction are often casualties of an “uncooperative” market.

Table 1 shows the return shortfall of dollar-weighted versus time-weighted value fund returns analysed by expense ratio size. Whereas active strategies cannot compete with passive index funds on fees, the less expensive strategies outpace the more expensive strategies by much more than the fee difference. Costs matter, as Jack Bogle constantly reminds us. It gets worse. The return penalty for investors is magnified for funds with the highest expense ratios, nearly three times that of the funds with the lowest expense ratios. The customers most easily seduced by high fees are clearly also the most avid performance chasers, embracing the funds after a run of strong performance and selling—too cheaply—when results have disappointed. Not only is the tendency to sell an underperforming position harmful to an investor’s total return, but the fees paid for active management exacerbate the loss.

Table 1. Shortfall Based on Expense Ratios (1991–2013) |

|||

Expense Ratio |

Dollar-Weighted Return |

Time-Weighted Return |

Shortfall |

Low |

7.88% |

9.22% |

–1.34% |

2 |

6.93% |

8.85% |

–1.92% |

3 |

6.07% |

8.35% |

–2.28% |

4 |

4.80% |

7.84% |

–3.03% |

High |

2.87% |

6.88% |

–4.01% |

Source: Hsu, Myers, and Whitby (2014). |

|||

Any use of the above content is subject to all important legal disclaimers and terms of use found at www.researchaffiliates.com, which are fully incorporated by reference as if set out herein at length. |

|||

The lesson that these observations holds for investors is to know yourself and your tolerance for risk or you are likely to be the “other side of the trade,” sacrificing return because it was too painful to hold a contrarian position through a market cycle.

The moniker “smart beta” initially described an improved method of capturing the market return—improved because it was intended to outperform cap-weighted benchmarks. Although beta cannot be smart or stupid, the ways we seek to embrace beta can be either. The cap-weighted index strategies are, naturally, “neutral beta” (or “bulk beta,” in the parlance of Towers Watson, the firm that invented the term “smart beta”). Although other so-called smart beta strategies predated the RAFI Fundamental Index, it was only after the success and acceptance of the Fundamental Index that these strategies were able to flourish. From what were initially relatively straightforward, diversified, and transparent strategies, the world of smart beta has evolved into a panoply of complex, narrowly focused, and often opaque strategies, all vying for investors’ attention and acceptance.

The worry for many defensive investors should be that sensible diversified index investing, a characteristic of the early smart beta strategies, is getting lost today as more specialised, factor-driven index-type strategies are being deployed. A portfolio composed of these investments is essentially a market-timing active portfolio, unaligned with Graham’s long-term value investing style. Worse, many investors will favour whichever of these niche factor-tilt strategies has offered the best recent performance, which takes them miles out of the Ben Graham camp.

Benjamin Graham’s well-reasoned, rules-based approach to security analysis remains, well after 80 years, a cornerstone for building a strong, long-term investment programme to meet investor’s financial goals. Similarly, the 10-year-old Fundamental Index strategy staunchly adheres to, and has delivered on, its promise to offer investors essential market exposure while outperforming a cap-weighted index over a market cycle.

Although over the last 10 years the annualised total returns of the FTSE RAFI Developed Ex US 1000 and FTSE RAFI 1000 indices have exceeded those of MSCI EAFE and S&P 500 indices, respectively, more recent performance has lagged these benchmarks. Does this mean that the Fundamental Index strategy is broken? Not at all. Recall Graham’s admonition to not sell holdings, especially on the downside, if their fundamentals remain sound. In fact, it is moments like this that adding to (or at least holding) a position can lead to higher returns at later points in the economic and market cycles.

In Graham’s own words: “You are neither right nor wrong because the crowd disagrees with you. You are right because your data and reasoning are right. In the world of securities, courage becomes the supreme virtue after adequate knowledge and a tested judgment are at hand” (Graham, 2006). If you are an investor who chooses to follow in the footsteps of Benjamin Graham, now is a propitious time to begin or to build on a core portfolio holding of the RAFI Fundamental Index strategy. The data and reasoning for doing so are in place. The final step is demonstrating the courage required to invest based on your knowledge and judgment.

Endnotes

- Research Affiliates, LLC, using CRSP and COMPUSTAT data.

- Kenneth French Data Library, using CRSP data.

References

Graham, Benjamin. 2006. The Intelligent Investor—Fourth Revised Edition. With new commentary by Jason Zwieg. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. First published in 1973.

Hsu, Jason C., Brett W. Myers, and Ryan J. Whitby. 2016. “Timing Poorly: A Guide to Generating Poor Returns While Investing in Successful Strategies.” Journal of Portfolio Management, vol. 42, no. 2(Winter):90–98.

Hsu, Jason, and Vivek Viswanathan. “Woe Betide the Value Investor.” Research Affiliates Fundamentals, February 2015.

Scott, Maria Crawford. 1996. “Value Investing: A Look at the Benjamin Graham Approach.” AAII Journal, (May):12–15.

Zweig, Jason. 2015. “Would Benjamin Graham Have Hated Index Funds?” Wall Street Journal (April 3).