Annexing Crimea, sponsoring a violent separatist movement in eastern Ukraine, and provoking many countries to impose economic sanctions—Russia has been in the headlines for the past nine months. In December the ruble fell by 32% in two days and the stock market fell by 22%. Both have since bounced back, largely recovering the short-term losses. While prudence cautions against concentrating one’s investments in Russia, current market prices offer alluring risk premiums. The ruble is cheap, interest rates are high, and dividend yields of Russian companies are among the highest in the world.

Investing in Russia has never been easy. In the 20th century, Russia defaulted twice, massively. Early in the century, the Bolsheviks seized all private capital. The previous owners lost not only their property but also their lives, if the Bolsheviks could find them. The disintegration of the Soviet Union at the end of the century produced a series of defaults. Western investors recall the 1998 default on government obligations that resulted in the collapse of Long-Term Capital Management. Those inside Russia remember the hyperinflation of the 1990s, which had the economic substance of a default by reallocating wealth from citizens to the government, and “privatization,” the redistribution of public property to a small group of new owners.

Today, Russia presents extreme risks and plentiful opportunities. The economic risk of low oil prices is compounded by risks arising from the country’s foreign policies and internal politics. The actions of Russia’s nationalist government in its ongoing conflict with Ukraine and the resulting economic sanctions imposed by the West are raising the odds of default. And yet, while markets are rightly fearful, Russia needs western capital and is willing to pay dearly for it.

Political Risk

With its vast and thinly populated area, Russia always feels threatened. Its political elite employs a security apparatus that seems paranoid to outsiders. Reflecting the fear that other powers plan to dismember the country, Russian foreign policy is oriented toward promoting puppet regimes in bordering countries. The leader of Kazakhstan has been in power for 25 years and the leader of Belarus for 20 years. These pro-Russian regimes in former Soviet states are undemocratic dictatorships, some with strong criminal inclinations.

Russia’s “friendly bordering dictator” doctrine is unstable and tends to backfire. When the populations of these bordering countries become fed up with the Russian-supported dictator and try to install a more responsive government, Russian authorities interpret the political movements as anti-Russian plots instigated by foreign intelligence services to undermine Russian security.

Internally, Russia’s political and civil institutions are centralized and archaic. Russia does not have an effective multiparty democracy; it is a one-party state. United Russia is a political machine for Vladimir Putin to direct the bureaucracy and drive legislation through the parliament. The principal competition is the Communist party, whose agenda is to re-nationalize the economy. The third largest party represents ultranationalists who espouse even harsher militaristic policies than Putin’s. To be sure, these other parties are more political theater than serious opposition.

Putin and his “party” control the Russian media. The stories told on TV remind western observers of Orwell’s novels. Russia tolerates a small nongovernmental media sector that allows independent voices to let off steam—but in a controlled way. The Russian government has learned that countenancing the appearance of unhampered thought enables it to control information even more effectively. Orwell did not foresee this tactic.

The Russian legal system is subservient to its political leadership. As a result, Russian companies, both state-owned and private, suffer from official corruption. Investors need to take financial reports with a grain of salt. A telling fact, in 2002 Gazprom received an Ig Nobel prize in economics for “adapting the mathematical concept of imaginary numbers for use in the business world.” To be fair, Gazprom shared its prize with Enron and many other companies. Nevertheless, investors scrutinize Russian financial reports with skepticism. As in other emerging markets (and a few developed markets too), the regime often redirects cash flow to its political priorities and away from investors.

Economic Risk

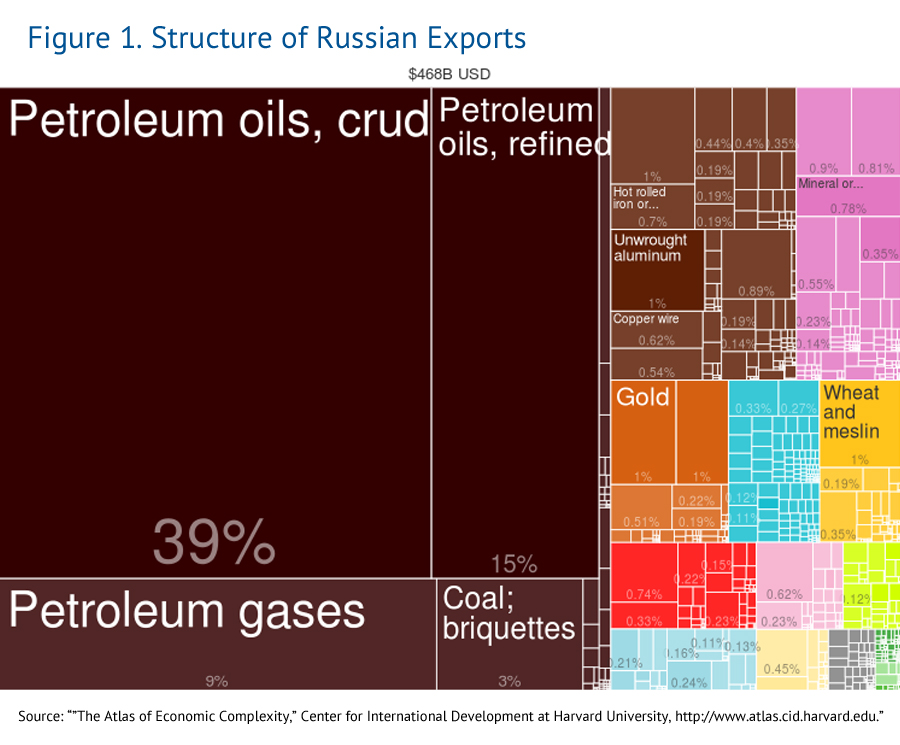

On a map of the world, Russia is hard to miss. It is the largest country by surface area. Nonetheless, Russia is sparsely populated and has an undiversified economy.1 Covering one-sixth of the dry surface of the earth, Russia holds huge reserves of mineral deposits. In international trade, Russia mainly focuses on exporting its natural resources. Close to 70% of Russian exports are energy related (see Figure 1). When energy prices fall, the country’s revenue stream tends to dry up.

The price of oil fell from $100 at the end of June 2014 to $60 in December 2014. This dramatic drop in fossil fuel prices is partly explained by technological advancements in natural gas and oil extraction in the United States, boosting supply, and partly by temporarily depressed demand due to slowing growth in China and Europe. The lower price of energy, Russia’s principal export, has certainly caused economic pain. But that’s not the whole story. Other countries that are heavily dependent on oil export revenues—for example, Norway and the United Arab Emirates—are not experiencing Russia’s levels of inflation, currency turmoil, and stock market instability.

Default Risk

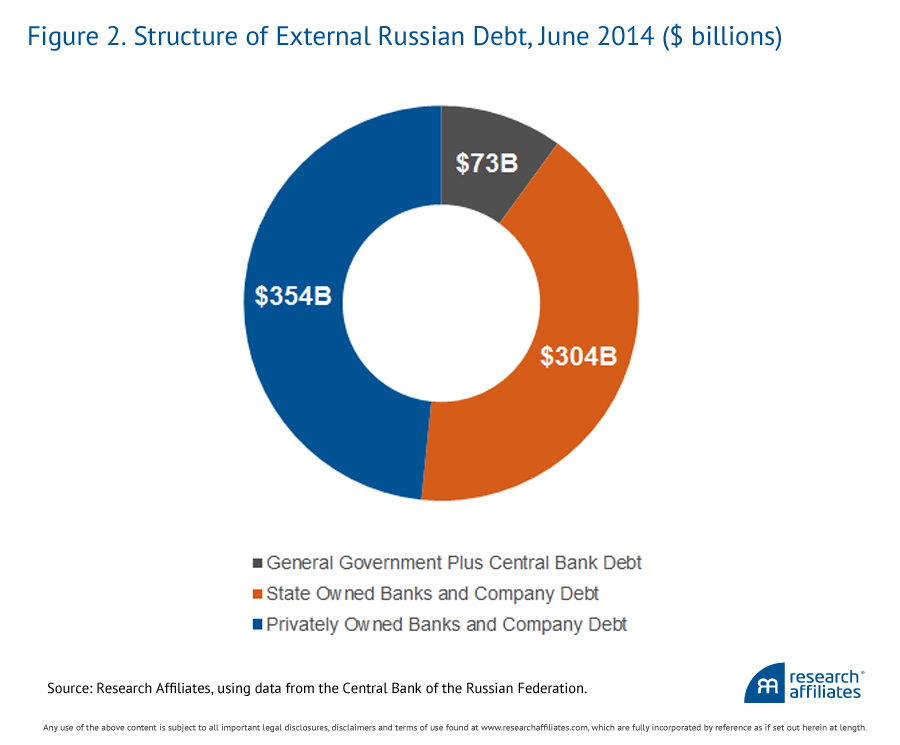

Why do investors fear a Russian default? To begin to understand today’s default risk, consider the structure of the Russian debt to outsiders, shown in Figure 2.

Russia’s current foreign debt is not large: $731 billion, or about 34% of Russia’s annual GDP. Direct government debt is $73 billion and state-owned banks and corporations owe an additional $304 billion. By international standards this is benign. U.S. external debt is close to 100% of GDP, for example. In consideration of Russia’s $478 billion currency reserves, accumulated over the past decade, it seems absurd to worry about default.2 Events in Ukraine, as much as the drop in oil prices, are the catalyst for the current Russian financial crisis. When Ukrainians decided to oppose the transformation of their government into another “friendly bordering dictator” regime, Russia annexed Crimea and instigated a militant separatist movement in eastern Ukraine. While the Georgian conflict in 2008 was short and limited in its effect on the Russian economy (Lawton and Beck, 2014), the Ukrainian conflict has had a much bigger impact. Russian and pro-Russian maneuvers resulted in thousands of deaths (including the 283 passengers and 15 crew members aboard a Malaysian airliner that was shot down in September 2014). In response, Western powers imposed economic sanctions.

To date, the sanctions have been relatively mild. They are nowhere close to the sanctions imposed on Iran, Cuba, or North Korea. Many countries, notably Germany, rely heavily on energy imports from Russia and oppose outright trade restrictions. European banks are ill positioned to absorb defaults on Russian debt. If the present Russian military line persists or becomes more aggressive, then there is room for significantly harsher sanctions; but under the comparatively weak sanctions now in force, Russian companies still generate sufficient revenue to service their debts.

Thus the present crisis is a solvency problem, not an inability to service debts. Many Russian companies need to refinance their hard-currency debts. Sanctions prohibit this refinancing. Russia’s biggest oil company, Rosneft, seems to have created the turmoil which caused the ruble to drop so sharply in December. According to the Financial Times (2014), Rosneft has $19.5 billion in debt due next year. If oil prices stay at the current $60 a barrel level, its revenue will cover only $15 billion; it is short $4.5 billion. Rosneft recently placed the equivalent of $10.8 billion in a ruble-denominated bond offering, and it is rumored that the company substantially converted the proceeds into dollars to replenish its reserves. Apparently, this transaction caused the recent panic in the currency and stock markets.

Rating agencies forecast a chain of bankruptcies and have already lowered Russian sovereign and private credit ratings. The Russian central bank has resorted to emergency measures. In addition to facilitating the Rosneft bond deal, it raised interest rates to 17% (from 10.5%) to make ruble accounts more attractive and discourage residents from converting rubles into foreign currencies.

Opportunity for Investors

Logically, this crisis should pass. Russia has ample internal reserves. Europe relies on Russian energy and it will take decades of infrastructure investment to lower this dependence. Russia needs foreign capital and foreign technology to improve its economic efficiency. Many sectors of the Russian economy are shockingly unproductive: A Russian worker is about 70% as productive as a Chinese worker and about 17% as productive as a U.S. worker.3 If the Russian government does not further escalate its intervention in Ukraine, or even softens its political position, then investors might profit handsomely from the current investment opportunities.

The Russian government can also afford, however, to advance a significantly tougher military policy in Ukraine. Russian citizens have endured rougher economic environments. When in the 1990s the income of ordinary Russians fell to African levels, many relied on homegrown vegetables to survive. Putin’s approval ratings today are at all-time highs (close to 85%). Those considering investing in Russia should recognize the rising risk of loss through default and/or nationalization. In investing, what is comfortable is rarely profitable. Investing in Russia now is definitely discomfiting, but it might pay off in the long run.

Endnotes

- Russia is the ninth largest country in the world (between Bangladesh, the eighth, and Japan, the tenth). Its population is mostly concentrated in the European part of the country. Russia is also ninth by total GDP (between Italy, the eighth, and India, the tenth).

- To understand incentives to default, it is helpful to consider the net investment position of Russia, or how much Russia owns outside its borders minus how much Russia owes to foreigners. The net investment position of Russia is approximately positive 9% (as of June 2014)—Russia owns more than it owes—and it is therefore not in its interest to default. For comparison, the net investment position of the United States is –38% (as of September 2014). Data sources: The Central Bank of the Russian Federation, the World Bank, and the U.S. Department of Commerce Bureau of Economic Analysis.

- Bush (2009) attributes the figures mentioned here to Strategy Partners, a Moscow management consultancy. He also refers to a survey conducted by McKinsey estimating a somewhat higher level of productivity: a Russian worker is 26% as productive as a U.S. worker.

References

Bush, Jason. 2009. “Why Is Russia’s Productivity So Low?” Bloomberg Businessweek (May 8).

Financial Times. 2014. “Rosneft and BP: Trading Problems.” December 17.

Lawton, Philip, and Noah Beck. 2014. “The Ukrainian Crisis: Should Investors Avoid the Russian Stock Market?” Research Affiliates (April).