The Ukrainian Crisis: Should Investors Avoid the Russian Stock Market?

Recent events in Crimea and eastern Ukraine raise questions about financial risk management as well as urgent political, military, and humanitarian issues. How has the riskiness of the Russian stock market changed? What can investors expect when Russia—or, for that matter, any other country—appears to be on the verge of armed hostilities? The Russian market, as represented by the MICEX index, has posted a total return of -11.3% since the crisis broke out on February 26th. Where will it go from here?

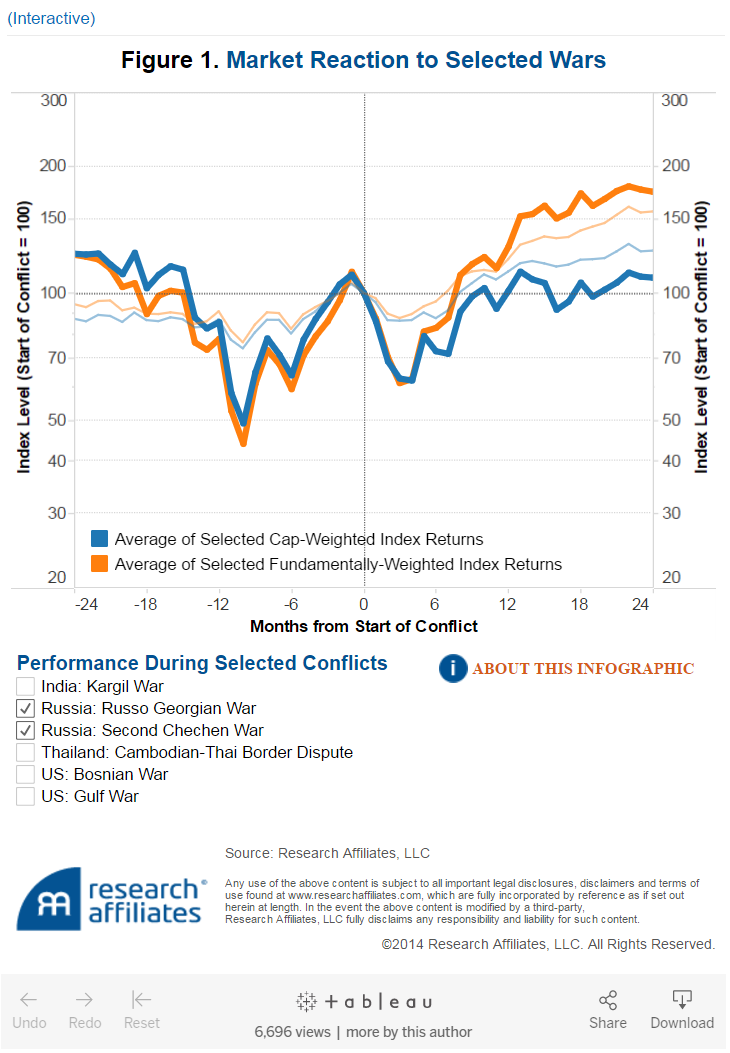

It is impossible to predict the outcome of an historical situation as complex and fraught as the Ukrainian crisis, but examining other modern conflicts might at least help in sizing up the market risk. Our research suggests that, when regionally contained wars break out, the negative impact is sharp but relatively short-lived. However, we also learned that the effect on portfolio returns depends in part on the investment strategy.

Six Recent Conflicts

We chose six modern-day conflicts for an event study of stock market reactions to military conflicts. In making these selections, we avoided frontier markets, limited ourselves to a timespan over which reliable data would be available, and sought wars whose scale would likely be large enough to have moved the affected countries’ financial markets. The United States was engaged in two of the selected conflicts; the other four involved emerging markets. In the interest of conservatism, we examined conflicts that were, we fervently hope, more extensive than the current Russian actions in Ukraine. In other words, we looked for potentially dangerous stock markets. With these criteria in mind, we observed the impact of events on the:

- U.S. market in response to the beginning of the Gulf War in 1990;

- U.S. market in response to the beginning of NATO involvement in the Bosnian War in 1994;

- Indian market in response to the Kargil War between India and Pakistan in 1999;

- Russian market in response to the beginning of the Second Chechen War in 1999;

- Thai market in response to the beginning of the Cambodian–Thai border dispute in 2008;

- Russian market in response to the Russo–Georgian war in 2008.

We aggregated financial data to profile the average market response in the period leading up to and following the outbreak of open hostilities.

Two Investment Strategies

For the purpose of this study, we distinguished between mainstream (procyclical) and contrarian (countercyclical) investment strategies.

A broad capitalization-weighted index is tautologically procyclical because it is, or very nearly is, the market portfolio. Allocations to individual stocks automatically increase when their prices advance and decline when they retreat; and the overall index return is the market return. A broad fundamentally weighted index, in comparison, is inherently countercyclical. Allocations to individual stocks are based on characteristics related to economic size but not to stock prices. The periodic rebalancing that is required to restore index holdings to their fundamental weights means selling stocks that have appreciated and buying stocks that have fallen in price—that is, in trading against the market.

Accordingly, in this exercise cap-weighted indices represent procyclical investing and fundamentally weighted strategies stand for countercyclical strategies.

Our Findings in Event Time

Figure 1 displays the aggregate effects, in event time, on cap-weighted and fundamentals-weighted indices.

This figure prompts some observations:

- On average, the markets we studied rose in the six months of sabre-rattling that preceded the start of the military campaigns.

- The markets fell sharply in the first two or three months after the beginning of the conflict.

- On average, stock prices remained depressed for up to six months but fully recovered eight months after the wars began.

- The average fundamentally weighted index modestly underperformed the cap-weighted index in the two years leading up to the conflict.

- When prices recovered, the fundamentally weighted index smartly outpaced the cap-weighted index.

And a provisional lesson:

After an average loss of 14% in the first three months of the conflict, procyclical and countercyclical investors alike may be powerfully inclined to pull money out of the country. But stocks sell at attractive prices in markets driven by fear. The subsequent outperformance of the fundamentally weighted index results from its systematically contrarian action in increasing exposure to stocks that have dropped in value. Fundamentally weighted strategies have the built-in discipline to buy low and sell high dispassionately.

This is neither to treat the profoundly worrisome crisis in Eastern Europe cavalierly nor to advocate profiting, however indirectly, from the distress of Ukraine, a sovereign nation whose people have suffered horribly over the last three-quarters of a century. It is merely to caution international investors that, from a strictly financial perspective, withdrawing assets from Russia might not be the right move.