Rob Arnott and Lillian Wu wrote that young workers are more likely than older ones to lose their jobs in an economic downturn. They are also prone to draw on their 401(k) plan to meet basic living expenses while they are unemployed. Given these facts, the early-phase concentration in equities—whose market prices are roughly correlated with the business cycle—makes target-date funds (TDFs) inordinately risky for young investors. A starter portfolio invested equally in mainstream stocks, mainstream bonds, and diversifying inflation hedges would be a safer option. In this article, Noah Beck considers TDFs in the broader context of workers’ total assets, including their own human capital.

The most famous brainteaser in history is the riddle of the Sphinx: What goes on four feet in the morning, two feet at noon, and three feet in the evening? Oedipus answers correctly: Man—who crawls on all fours as a baby, walks on two feet as an adult, and needs a walking stick in old age. If modern life were similarly compressed into one day, today’s millennial generation would be headed off to work—grabbing that cup of coffee, booting up the computer, and setting their priorities for the day. Their parents, the baby boomers, are getting ready to clock out—writing some last-minute emails, gathering their belongings, and looking forward to a pleasant, restful evening at home. The two generations are at the opposite ends of their working lives, with the millennials building their careers and the boomers on the doorstep of retirement and with Gen X somewhere in the middle.

Naturally, one would expect their retirement portfolios to look very different. The baby boomers ought to have the bulk of their portfolio in fixed income securities, while the millennials should be invested more aggressively—almost exclusively in stocks. Right?

Maybe not.

Conventional wisdom tells us to put retirement investments on a glidepath, with decreasing equity risk as our retirement date draws near. We’ve garnered considerable attention (and ruffled a lot of industry feathers) by showing that this conventional view is seriously flawed.1 Even so, two-thirds of a trillion dollars in assets are now invested on the untested premise that young people can and should take more risk than their middle-aged colleagues, in glidepath products known as target-date funds (TDFs). TDFs are typically offered as a one-size-fits-all investment vehicle that employees can select in their defined contribution (DC) retirement plans. In many cases they are the default option. TDFs typically start out with a heavy concentration in equities but progressively transition into predominantly fixed income securities over the years leading up to the plan participant’s expected retirement date.

There are plenty of problems with target-date funds; I’ll only address one of them here. TDFs operate under the tacit assumption that they are the only asset in an employee’s retirement kitty. That assumption is almost always false.

The Big Picture

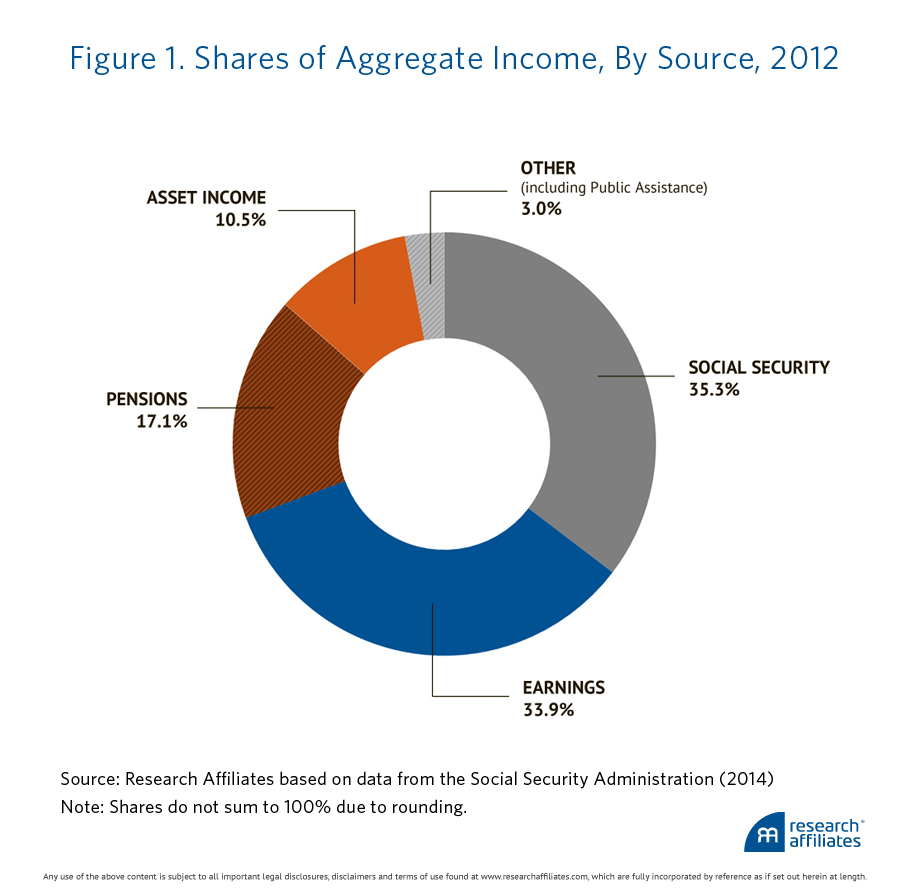

Even if a TDF is the only pension that one owns, income from that pension portfolio makes up only a small portion of total income for people over 65. The majority comes from social security, defined benefit pensions, income earned on other assets, and wages, which together already act as the glidepath that the conventional wisdom advocates. Figure 1 shows the breakdown for the current retirement age population according to the U.S. Social Security Administration.

Social Security checks account for over a third of the average retiree’s income. This income is virtually guaranteed2 and adjusts for inflation as the recipient ages. If we had to categorize all assets and income streams as “stock-like” or “bond-like” in terms of expected future cash flows, the income from Social Security is very similar to owning an inflation indexed bond (or TIPS). Because income from Social Security depends on how many years a person worked, boomers have a substantial allocation of their total retirement pool to Social Security “bonds.” Do they need more bonds in their TDF holdings? Not so sure. Millennials, still at an early point in their careers, would currently have next to none.

Pension distributions make up another sixth of the pie for current retirees, and defined benefit (DB) pension distributions are also bond-like in nature. Generally the DB plan sponsor assumes the risk of the underlying portfolio and provides the employee with either a guaranteed lump sum or an annuity upon retirement. The value of this benefit, like Social Security, grows the longer you work and the more you earn. DB plans are becoming increasingly rare for new employees, but even for millennials who are lucky enough to have one, its present value would currently be quite low. Boomers with pensions, however, have a second substantial bond-like asset in their overall retirement portfolios.

There is a third asset, crucial to retirement preparedness, in which millennials actually have an advantage over their parents: their own human capital. Boomers who are nearing retirement may only have a precious few years of work remaining; their human capital is largely depleted. But, millennials have decades of employment income ahead of them. They clearly have the higher present value of all future earnings.

How should we categorize this human capital? For most individuals, employment income increases slightly faster than inflation, is more certain in the short term than the long run, and can potentially diminish or even disappear during a recession. Does this sound more like a U.S. Treasury bond or a dividend-paying stock? We would submit that, in terms of expected cash flows, it is much more like stock—a stock in which the millennial has a very high concentration, and the boomer, relatively little.

Lastly, retirement assets like social security, pensions, and human capital are only one side of an individual’s personal balance sheet. It is also important to consider debt. In most cases, millennials just beginning their adult life are saddled with debt from investing in their education and buying that first car or house. As people age, they make payments toward those liabilities, in effect buying back their own bonds and deleveraging their balance sheet. Retirees generally have very little debt remaining; some even have none left at all and live rent- and mortgage-free in their own home. Should boomers that are buying down their debt also be compelled to buy additional debt securities (a.k.a., bonds) in a TDF?

For those of you keeping score, here is the final tally of income-generating assets that reside outside your 401(k) plan. Baby boomers have built up a sizeable bond-like portfolio in the form of social security and pension income, which accounts for over 50% of income for today’s retirees (and much more for lower income individuals). Millennials’ largest asset is their ability to earn a paycheck, presumably for decades to come, an ability that is like a dividend-paying asset which will ebb and flow with the economy like a common stock. On top of that, millennials’ assets are typically levered up with debt, while the boomers are aggressively deleveraging as they approach retirement. If the conventional goal is to have a riskier balance sheet as a young adult and a safer one as a senior, then that goal has already been accomplished outside one’s DC plan. For many investors, the glidepath to retirement is already in place.

The Big Question

How then should millennials and boomers invest their individual accounts and DC assets? The answer of course depends on their individual Social Security, pension, and employment situation, but on average, the two generations should be investing in portfolios that are much more alike than the TDF scheme prescribes. For example, baby boomers who expect to receive 40% of their retirement income from bond-like sources such as Social Security and defined benefit distributions might consider dividing their remaining assets more or less equally among mainstream stocks, mainstream bonds, and a third pillar of inflation-hedging assets such as TIPs, high-yield bonds, and low volatility equities. Rob Arnott and Lillian Wu (2014) recently suggested that millennials’ early forays into investing would potentially also be well served by similar allocations across those three classes—mainstream stocks for growth, mainstream bonds as a hedge against a temporary impairment of human capital (a.k.a., unemployment), and a third pillar of inflation hedges that might be expanded to include emerging market stocks, bonds, and currencies.

Specific asset mix decisions, both over the course of a life at work and in retirement, importantly depend on the individual’s total financial situation. Boomers with large DC portfolios may want to hold more bonds or third pillar assets, while low-income seniors who expect the preponderance of their income to come from Social Security may want to invest their modest retirement funds entirely in stocks with sustainable dividends. There is unfortunately no one-size-fits-all portfolio for any given target retirement date; we need to abandon that illusion. Even if there were, it would likely need a flatter glidepath than the ones available in the market today, or potentially none at all, due to the bond-like assets already held by boomers and the equity-like assets already held by millennials.

Conclusion

In the Sphinx’s riddle, the life of man is compressed into a single day. Perhaps a modern day Sphinx (admittedly a less cryptic and mysterious one) would pose a similar riddle: Who owns an equity centric portfolio in the morning, a balanced portfolio at noon, and a fixed income portfolio in the evening? At first blush, one might be tempted to answer “the holder of a target-date fund.” But a much more accurate answer would be “everyone.” Maybe millennials and boomers aren’t so different after all.

Endnotes

- See Arnott, Sherrerd, and Wu (2013), and Estrada (2014).

- Even with the means testing that we surmise is probably coming, Social Security will still be available for those who don’t have access to substantial other income and assets.

Further Reading

Arnott, Rob. 2011. “The Long View—Building the 3-D Shelter.” Research Affiliates (October).

———. 2012. “The Glidepath Illusion.” Research Affiliates (September).

Arnott, Robert D., Katrina F. Sherrerd, and Lillian Wu. 2013. “The Glidepath Illusion… And Potential Solutions.” Journal of Retirement, vol. 1, no. 2 (Fall):13–28.

Arnott, Rob and Lillian Wu. 2014. “What Are We Doing to Our Young Investors?” Research Affiliates (October).

Estrada, Javier. 2014. “The Glidepath Illusion: An International Perspective.” Journal of Portfolio Management, vol. 40, no. 4 (Summer):52–64.

Social Security Administration, Income of the Aged Chartbook, 2012, SSA Publication No. 13-11727, April 2014.

Treussard, Jonathan. 2014. “Target-Date Funds: No Happily Ever After in This Fairy Tale.” Research Affiliates (July).