Everything Everywhere All at Once: Conglomerates and the Disappearing Diversification Discount

Conglomerates have historically suffered from a “diversification discount” wherein the whole of the company is worth between 13% and 15% less than the sum of its parts.

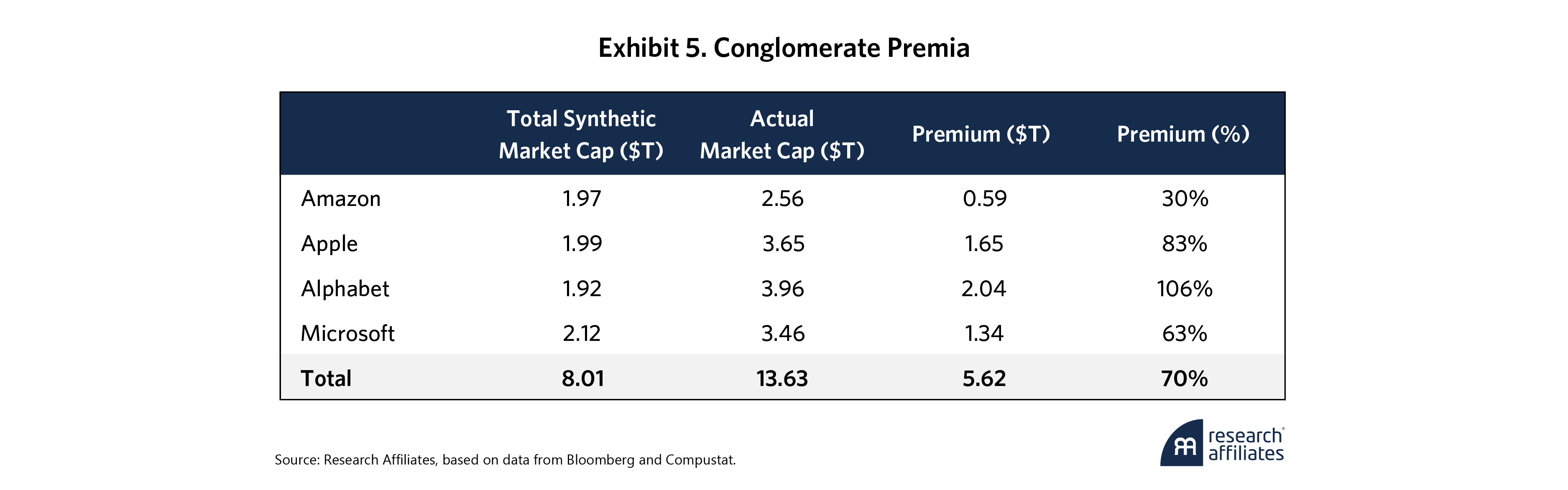

In a break with past patterns, modern conglomerates Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft average a 70% “diversification premium,” with their valuations exceeding the total combined “synthetic market caps” of their underlying business lines by $5.62 trillion.

The 70% diversification premium of today’s mega-cap tech conglomerates may be the result of more valuable synergies, the market’s faith in their leadership teams, or rosy expectations about their prospects, that they will be among the big winners of the artificial intelligence (AI) revolution, for example.

Whether these diversified firms can maintain their positions indefinitely is an open question, but market history suggests the competition always catches up.

For more than 100 years, General Electric (GE) stood at the forefront of technological innovation. Founded in 1892 with the merger of the Thomas Edison Companies, which had already given us the first practical light bulb and the first U.S. central power stations, GE went on to develop locomotives and X-ray machines and the first mass-produced refrigerators, television sets, and automatic washing machines. It also became a pioneer in jet engines, nuclear reactors, CT scans, and MRI machines, and GE scientists earned Nobel prizes in chemistry and physics for their discoveries. By the 1970s, the company dominated energy, aviation, materials, and health care technology, among other sectors.

Create your free account or log in to keep reading.

Register or Log in

In the 1980s and 1990s, under CEO Jack Welch, GE further diversified into financial services and even, through its acquisition of RCA, which owned NBC, entertainment and media. Welch was heralded as “Manager of the Century” by Fortune for his aggressive leadership style and GE’s exceptional performance. The hit NBC show 30 Rock brilliantly parodied its own parent company’s divergent businesses and fiercely competitive corporate culture in the character of Jack Donaghy, GE’s “Vice President of East Coast Television and Microwave Oven Programming.”

The poster child of the late 20th-century conglomerate, GE was a one-stop shop for household appliances, medical devices, jet engines, sitcoms, and home loans. But GE was hardly an outlier, then or now. In fact, conglomeration is a natural evolutionary stage in the lifecycle of mature, successful companies. As a firm rises to the top of its sector, often the only direction for expansion is away from its core competencies and into tangential businesses or even wholly unrelated ones.

[C]onglomeration is a natural evolutionary stage in the lifecycle of mature, successful companies. As a firm rises to the top of its sector, often the only direction for expansion is away from its core competencies and into tangential businesses or even wholly unrelated ones.

”Many of today’s era-defining mega-cap companies have entered their conglomerate phase. Amazon is a representative example. Established as an online bookstore, Amazon came to dominate e-retail and expanded into cloud computing, Prime Video, music, and gaming. From Kindle e-readers, it diversified into Fire tablets and TV, Alexa-powered Echo smart speakers, and Ring doorbells and security cameras. Amazon also provides advertising, payment, lending, logistics, pharmacy, and telehealth services. Through Whole Foods and Amazon Fresh, it has waded into the notoriously difficult grocery and supermarket business. Taking a page from GE, Amazon acquired MGM Studios in 2022 and added its extensive media library to its already expansive Prime Video catalogue.

Amazon still isn’t finished. Today, it is launching satellites for global broadband internet and developing artificial intelligence (AI)-powered health care, as well as building proprietary robotics for warehouse automation and small modular nuclear reactors to power its data centers and AI/cloud infrastructure, among other projects.

But Amazon isn’t alone. Alphabet, Apple, and Microsoft are all similarly positioned, having evolved from search, personal computer (PC), and operating systems specialists, respectively, into Amazon-like conglomerates with cloud computing, entertainment, health care, biotech, banking, and AI business lines. Together, these four companies comprise about 20% of the U.S. large-cap market.

The Conglomerates Literature

Companies with such all-encompassing ambitions and disparate product lines have not always been rewarded. According to the financial research, conglomerates generally trade at a “diversification discount.” Their market value is typically lower than the implied total of their stand-alone business lines. Two foundational studies established the baseline empirical finding that diversification often fails to create shareholder value. Lang and Stulz (1994) demonstrate that diversified firms have lower Tobin’s Q ratios than their more focused counterparts, suggesting that the market may penalize complexity and potentially inefficient internal capital allocation. Berger and Ofek (1995) reinforce this result. They calculate that diversified firms are worth roughly 13% to 15% less than the sum of their parts due to investment distortions, agency problems, and the cross-subsidization of weaker business segments.

According to the financial research, conglomerates generally trade at a ‘diversification discount.’ Their market value is typically lower than the implied total of their stand-alone business lines.

”Subsequent research into the existence of the diversification discount has identified endogeneity of the diversification decision as an important consideration. Diversification may not produce underperformance so much as some firms with declining core businesses may diversify in response to such weakness (Campa and Kedia, 2002). Other research indicates that measurement issues, such as how segment values are calculated, can impact the observed discount (Villalonga, 2004). Still, the literature has identified managerial empire building, misallocation within internal capital markets, reduced transparency, and governance frictions, among other factors, as contributing to lower valuations. While diversification may create value in certain environments and for companies with particular characteristics, conglomerates have historically traded at a significant and persistent discount relative to comparable firms with a single core business focus.

Today’s Conglomerates

How do modern 21st-century conglomerates stack up against their traditionally discounted forerunners? First, we quantify how diversified Amazon, Apple, Alphabet, and Microsoft are today versus 10 years ago. Exhibit 1 shows each firm’s revenues decomposed by product line in 2015 and their most recent fiscal year, on the left and right, respectively. The middle graphic charts how revenues from each division have evolved over the decade.

Microsoft was already a well-diversified conglomerate at the start of our sample, while Amazon, Apple, and Alphabet were well on their way. All four firms rapidly grew their revenues over the decade, with their diversifying segments driving a disproportionate share of that expansion. Amazon, for example, tripled the revenues of its core business, online stores, but its third-party seller services business line, which includes brand building, enhanced content, analytics, and fulfillment services, saw an almost tenfold increase from $16 billion to $156 billion. Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Amazon Prime and other subscription services similarly soared from $8 billion to $108 billion and $4 billion to $44 billion, respectively.

Apple services revenue, from App Store, Apple Pay, Apple TV, Apple Music, and iCloud, more than quintupled, from $20 billion to $109 billion. Alphabet’s YouTube business, which it acquired in 2006, went from $6 billion to $36 billion, and its Google Cloud Platform emerged as its second-largest revenue generator after search. Incidentally, in the first year of our sample, 2015, Google renamed itself Alphabet to reflect its expanding portfolio of underlying businesses.

Exhibit 2 shows how the diversification of business lines of all four companies has increased over the 10 years, as shown by the effective number of segments.1 As of fiscal year 2024, Amazon is the new leader, with the highest effective number, and Alphabet and Apple are now about as diversified as Microsoft.

A Simple Check of Conglomerate Valuations

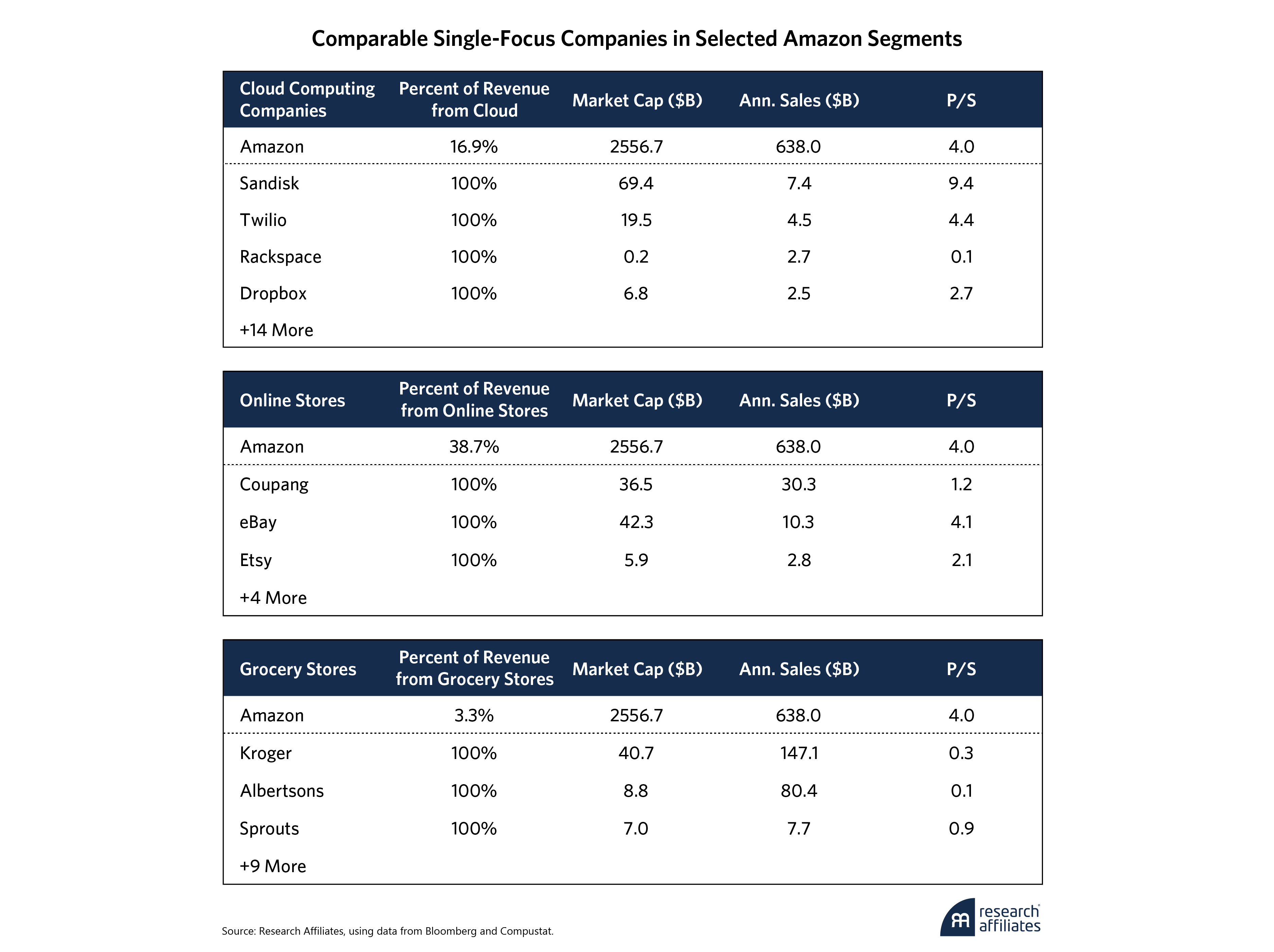

After dividing the conglomerates into their individual business lines, how do the valuations compare to that of their single-segment peers? We first classify each business segment according to its Bloomberg Industry Classification Standard (BICS) and identify all other companies that focus exclusively on that sector. We define these as U.S. firms that classify at least 90% of their sales under the same BICS category as the segment in question. For example, Amazon’s cloud computing (AWS) business line competes with such single-segment cloud counterparts as Twilio, Rackspace, and Dropbox; its online stores compete with eBay, Coupang, and Etsy; and its grocery business with Kroger, Albertsons, and Sprouts. (Appendix 1 takes a deeper look at these companies’ market caps, sales, and price-to-sales (P/S) ratios.)

In each segment, we merge all comparable one-segment companies into a single hypothetical firm and calculate its P/S ratio by dividing its combined market cap by its total annual sales.2

Exhibit 3 shows the resulting segment-level P/S ratios for each conglomerate’s corresponding lines of business, with each company’s actual P/S ratio in green.

Based on these results, what would the market capitalizations of the products and services of each conglomerate be if they were stand-alone companies? How much would Alphabet’s YouTube Ads business be worth, for example, if it had the same P/S ratio as FuboTV, Spotify, and other firms in the online ads sector? YouTube generated $36 billion in advertising revenue in 2024, about 10% of Alphabet’s total. As its own company with a P/S ratio of 5.8 (the average P/S of YouTube’s single-segment competitors), YouTube would have a $209-billion market cap. Since YouTube is not a tradeable security and has no actual market capitalization, we call this its “synthetic market cap.”

We estimate the conglomerate’s total market value by adding up all the synthetic market caps of its business lines and determine whether it is priced at a premium or discount by comparing that to the firm’s actual market cap.

Exhibit 4 shows the synthetic market caps of the various business lines of Amazon, Apple, Alphabet, and Microsoft as a fraction of actual total market cap. Any white space represents excess market cap beyond the sum of each segment’s synthetic market cap. This is the diversification premium at which the conglomerate is trading and measures how much greater the company is priced over the sum of its parts.

All four conglomerates have a sizable premium relative to their competitors in corresponding business segments. Exhibit 5 shows just how large a premium in both dollars and percentages. With an average premium of 70%, today’s mega-cap conglomerates may be pricing in more than $5 trillion of additional value.

With an average premium of 70%, today’s mega-cap conglomerates may be pricing in more than $5 trillion of additional value.

”Just Another “Tech Is Expensive” Story?

What explains today’s diversification premium? On the one hand, perhaps these companies should be pricier. After all, countless news items have chronicled how expensive the U.S. stock market has become, with tech companies leading the way. On the other hand, our valuation comparison is apples to apples, and save for Amazon’s grocery business, tech company to tech company. It includes internet services like Uber and Doordash, cloud companies like Sandisk and Dropbox, streaming services like Spotify, and software companies like Salesforce and Palantir. So, even if the U.S. market is trading rich, and the tech sector carries a premium on top of that, this could be an additional premium on top of U.S. tech, an extra expense to buy the technology businesses run by the largest conglomerates at the top of the market.

But remember, conglomerates have historically come without any premium at all. Priced at a roughly 15% discount, conglomerates of past decades have often been perceived as, at best, boring, watered-down baskets of semi-related businesses and, at worst, the products of empire-building executives overpaying for poor or negative cash-flowing enterprises. So, what makes today’s conglomerates so different?

Maybe they benefit from better synergies than their predecessors. After all, GE’s health care division might not have boosted the value of its aviation business or vice versa. Why would keeping them under the same umbrella command a premium? By contrast, today’s conglomerates’ business lines may present more opportunities for cross-pollination and tech-driven synergy. For example, the data that Alphabet gathers from its Google accounts and search queries may improve how it targets its YouTube Ads, making them more valuable to advertisers, and the iPhone automatically funnels users into the Apple ecosystem and its Apple Pay and Apple Music services.

While these relationships increase the total revenues generated by these business lines, our decomposition already takes that into account. Without Google’s data making each ad more valuable to advertisers, for example, YouTube might not have commanded the $36 billion in revenue that it did for 2024. The only remaining consideration is the cost of generating those sales, which should also benefit from any inter-segment synergies. For example, by directing iPhone users into Apple Pay, Apple avoided the marketing costs that competing digital payment services would incur to attract new users. Such cost savings suggest that YouTube Ads and Apple Services should cost more per dollar of sales and that their respective $209 billion and $577 billion market cap estimates might be low. But even if we double the price-to-sales assumptions for those businesses, a generous adjustment for some synergistic cost savings vs. their peers, it still wouldn’t explain the $2.0 trillion and $1.6 trillion premia for Alphabet and Apple, respectively.

Another potential culprit could be the nature of these conglomerates’ latest bets. While much of their revenue comes from their core products (Amazon’s retail, Apple’s iPhones, Google search, and Microsoft Office and Windows), much of their valuation may come from the prospects of their future projects. The jury is still out on which companies will benefit most from the AI revolution. But the market could be placing a $5.6 trillion bet that our big four conglomerates will beat out the more specialized players in the space as well as any newcomers.

There is another possibility. Maybe the diversification premium represents a vote of confidence in these firms’ executive leadership. Trillion-dollar companies often come with celebrity CEOs and celebrity founders. Sometimes these executives are perceived as skilled portfolio managers with a knack for picking winners. As such, owning a conglomerate’s stock is more like owning an exchange-traded fund (ETF). Investors are willing to pay more for the privilege, just as they would for the services of famous money managers in decades past. Perhaps the market is relying on tech CEOs to spot tomorrow’s successful companies before the average investor and either buy out those businesses or commit enough capital early enough to beat them to market. Of course, while such foresight could certainly account for some additional value, a 70% premium like the one we see today would be a bit steep even for the services of the most legendary investors.

So, What’s Next?

Does such a large conglomerate premium mean these companies all face an imminent correction? Not necessarily. While we wouldn’t presume we could predict the short-term price movements of any asset, we can look to past data to make as well-informed a decision as we can. Historically, conglomerates have traded at a slight discount. Today, they trade at a significant premium. Reversion to the mean may not be inevitable, but neither should it come as a surprise.

GE’s experience may offer some perspective. As the 21st century commenced, the GE empire continued to swell. GE Capital, for example, functioned as a bank, but without the regulatory oversight, and expanded until it generated half the company’s profit. It piled risk upon risk, in commercial real estate, subprime lending, and insurance, just in time for the global financial crisis (GFC). GE also doubled down on its strategy of acquiring energy-related assets. As oil prices crashed, GE obscured earnings shortfalls with opaque accounting.

The company withered. In 2018, after more than a century on the benchmark index, GE fell off the Dow Jones Industrial Average. In 2024, what remained of Thomas Edison’s General Electric was spun off into three separate firms.

Of course, not every conglomerate is doomed to such a fate. Only time will tell how long any company can remain number one in its sector or sectors. But the data is telling: As Arnott and Wu (2012) demonstrate, the top dogs have bullseyes on their backs. Targeted by competitors and governments alike, their growth tends to lag until they are eventually overtaken by a relentless pack of newcomers.

The Trillion-Dollar Question

For today’s mega-conglomerate top dogs, the trillion-dollar question is, Can the competition catch up? History’s answer is unequivocal: The competition always catches up. But then again, maybe today’s tech conglomerates are different. Maybe they will maintain their market dominance and continue to be everything everywhere all at once.

Please read our disclosures concurrent with this publication: https://www.researchaffiliates.com/legal/disclosures#investment-adviser-disclosure-and-disclaimers.

Appendix

End Notes

1. Effective number is a diversification measure defined as the inverse of the sum of the squared weights, \(\frac{1}{\sum_{i=1}^{N} w_i^{2}}\). In the denominator, the sum of the squared weights, also called the Herfindahl index, is the weighted average of the weights themselves and can be interpreted as the typical weight that the conglomerate has in each business segment. A company with small weights across multiple divisions will have a small average weight and a high effective number. A company with, say, 95% of its weight in one segment and 1% each in five others, however, will have a weighted average weight of about 90% and an effective number of 1/0.9, or about 1.1 segments. This company would have slightly more than one business line despite a simple count of six segments.

2. This is mathematically identical to taking the market-cap-weighted average of the sales-to-price (S/P) ratio of each company i and inverting the average to calculate a segment’s P/S ratio.

References

Arnott, Robert D., and Lillian J. Wu. 2012. “The Winner’s Curse: Too Big to Succeed?” Journal of Indexes 42–51, 64.

Berger, Philip G., and Eli Ofek. 1995. “Diversification’s Effect on Firm Value.” Journal of Financial Economics 37 (1), 39–65.

Campa, José M., and Simi Kedia. 2002. “Explaining the Diversification Discount.” The Journal of Finance 57 (4), 1731–1762.

Lang, Larry H. P., and René M. Stulz. 1994. “Tobin’s q, Corporate Diversification, and Firm Performance.” Journal of Political Economy 102 (6), 1248–1280.

Villalonga, Belén. 2004. “Diversification Discount or Premium? New Evidence from the Business Information Tracking Series.” The Journal of Finance 59 (2), 479–506.