Financialization: How Deficits Inflate Profits and Equity Valuations

U.S. fiscal deficits fund rising entitlement spending that stimulates consumption and increases the growth rate of corporate profits.

In the financialized U.S. economy, each dollar of deficit spending may flow into a dollar of corporate profit.

Research shows that the mechanical reinvestment of rising profit distributions into price-inelastic index funds has directly inflated market valuations.

With profits and valuations sustained by rising deficit spending, the stock market is likely vulnerable to a severe correction when that fiscal support is withdrawn.

This article is adapted from the longer paper, “Financialization: How Deficits Inflate Profits and Equity Valuations,” posted to SSRN.

The mid-twentieth-century U.S. economy was built on a foundation of robust domestic saving and investment that created a virtuous cycle of broadly shared growth in prosperity. Seventy years later, that foundation has eroded. Corporate profits and equity valuations have soared even as the net investment that once propelled growth has fallen by more than half. What explains this paradox?

Create your free account or log in to keep reading.

Register or Log in

The answer is the financialization of the economy. Chronic fiscal deficits used to fund rising social transfers stimulate consumption and flow into profits, as explained by the Kalecki-Levy profit equation. Next, decoupled from productive investment, rising profits are recycled back into financial assets through price insensitive passive funds, thereby inflating market valuations.

While rising monopoly power, globalization, and technological innovation, among other factors, may explain which firms prosper, we describe the overarching macroeconomic process that leads aggregate corporate profits to expand at a faster pace than the underlying economy.1

How Deficits Create Profits

The Kalecki–Levy profit equation (Kalecki, 1942; Levy, 2012), a fundamental accounting identity of the aggregate economy, explains how persistent deficit spending may flow directly into corporate profits.

This identity shows that an economy's spending and income must balance. When businesses invest, their spending becomes income for other firms and thus boosts profits. Conversely, when households save more, they spend less on goods and services, which reduces corporate revenues and profits. A government deficit is negative saving. When the government spends more than it takes in through taxes, it stimulates income and profits.

A government deficit is negative saving. When the government spends more than it takes in through taxes, it stimulates income and profits.

”With fiscal deficits, the Treasury deposits net financial wealth into the private sector. The wealthy owners of these new securities just swap one financial asset for another, cash for Treasuries. The proceeds from selling these newly issued government securities fund transfer payments, primarily Social Security and Medicare, to the far larger cohort of relatively lower-income households that spend most of their income, which stimulates aggregate consumption.

As recipients of transfers spend their newly minted income, corporations record the receipts of that spending as revenue. Because this financial stimulus does not cause a corresponding rise in production cost, most of that revenue flows to the bottom line as profits.

The economic context is key to the financialization process. Cyclical deficits during recessions may mobilize idle resources. But for the last half century, the U.S. government incurred chronically rising deficits throughout the business cycle, even when the economy was at or near full capacity. When real resources are nearly fully deployed, additional financial income from deficit spending does not generate significant new real investment.

Because new financial profits exceed profitable investment opportunities, corporations do not increase their investment and must either retain or distribute those new profits. As Lazonick (2014) demonstrates, during the past five decades, firms distributed these profits to shareholders. This shift in corporate behavior is the essence of financialization.

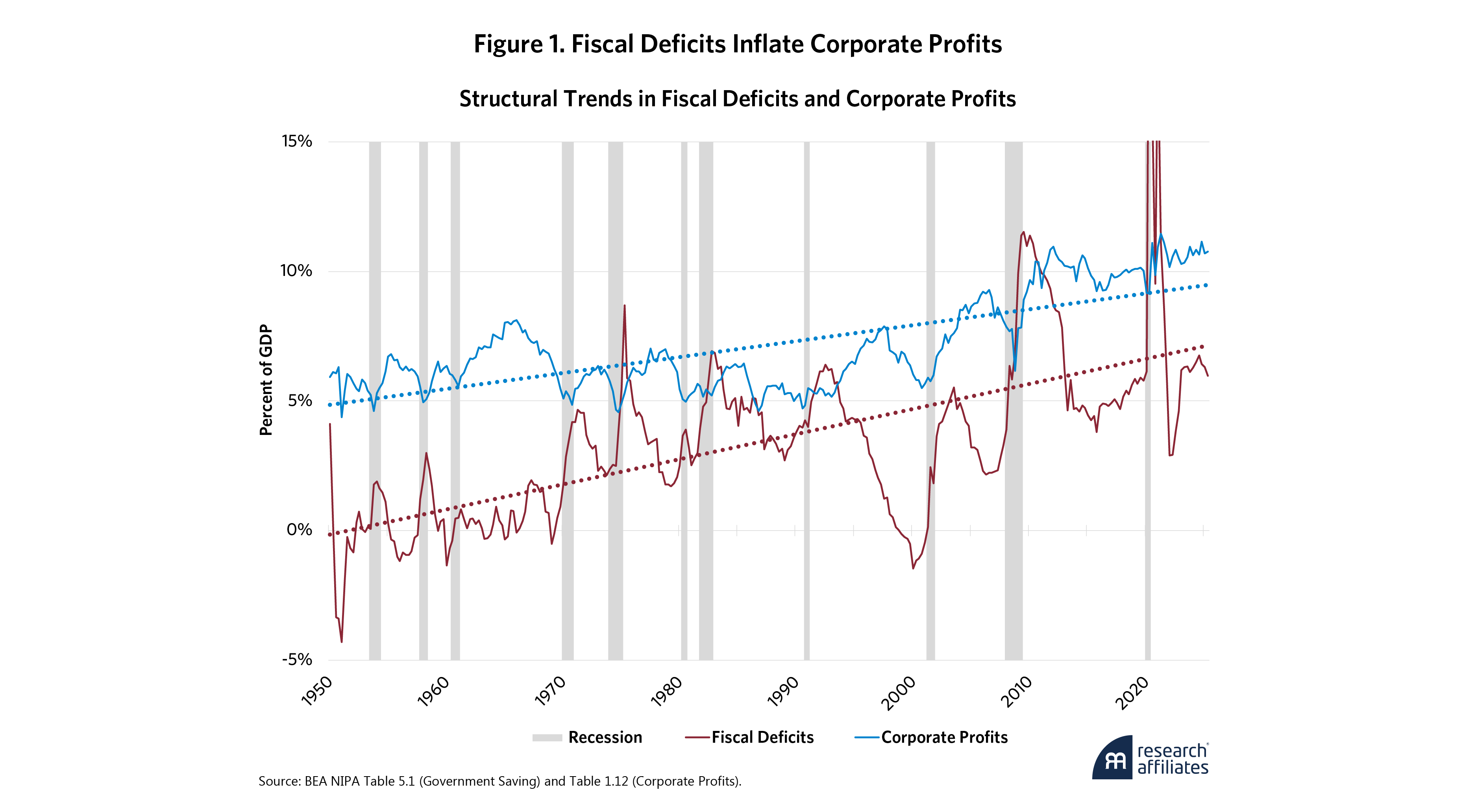

What evidence ties U.S. fiscal deficits to corporate profits? A simple quarterly correlation between the two variables is misleading. Exhibit 1 shows recessions have consistently produced a negative cyclical relationship in which falling profits coincide with rising deficits.

This short-term inverse correlation, however, masks the long-term positive structural relationship predicted by the Kalecki-Levy profit equation. We find a statistically significant, nearly one-for-one long-run relationship between fiscal deficits and corporate profits (Brightman and Pickard, 2025).

We find a statistically significant, nearly one-for-one long-run relationship between fiscal deficits and corporate profits.

”A powerful "natural experiment" confirms this long-term relationship. The U.S. government briefly ran brief budget surpluses in the late 1990s, withdrawing net spending from the economy. During this period of declining deficits and brief surpluses, corporate profits fell too. But with the recession in 2001, fiscal deficits returned and profits immediately resumed their upward climb.

This natural experiment, combined with the Kalecki-Levy theoretical framework and confirmed by our econometric results, supports our directional deficits-to-profits interpretation. We conclude fiscal policy is responsible for the long-term ascent of corporate profits as a share of GDP.

How Profits Inflate Valuations

Having described how deficits create financial profits, we now explain how these deficit-fueled profits are capitalized into higher market valuations.

The rise of institutional investing agents has created a financial system that directs financial saving flows into price inelastic passive index funds (Brightman and Harvey, 2025). Mandated to remain fully invested, these funds then recycle the inflows to purchase stocks in proportion to their market capitalization indifferent to valuation, thus bidding up prices without any change in fundamentals. Gabaix and Koijen (2021) formalize this process in their “inelastic markets hypothesis”.

This inelastic-flow mechanism does not operate in isolation. The secular decline in real interest rates boosts valuations by increasing the present value of expected future earnings.

For decades, U.S. financial profits grew faster than investment opportunities and as firms distributed these excess profits to wealthy households, they added to the rising flows into index funds. Studies with different methodologies confirm that these large, price-indifferent flows had a disproportionate influence on market valuations. Ben-Rephael, Kandel, and Wohl (2012), document persistent valuation effects from mutual fund flows and Gabaix and Koijen’s structural model estimates each $1 of inflow increases market value by roughly $5.

For decades, U.S. financial profits grew faster than investment opportunities and as firms distributed these excess profits to wealthy households, they added to the rising flows into index funds.

”The History of Deficit-Driven Financialization

Two distinct forces working together contributed to the financialization of the U.S. economy. Rising deficit spending generated excess profits while falling interest rates determined what companies did with those profits. Had interest rates and returns on physical capital remained high, firms might have funded capital expenditures with these profits. Instead, low interest rates and low expected returns on investment encouraged them to reinject these profits back into the financial markets.

Two distinct forces working together financialized the U.S. economy. Rising deficit spending generated excess profits while falling interest rates determined what companies did with those profits.

”Collapse of National Saving

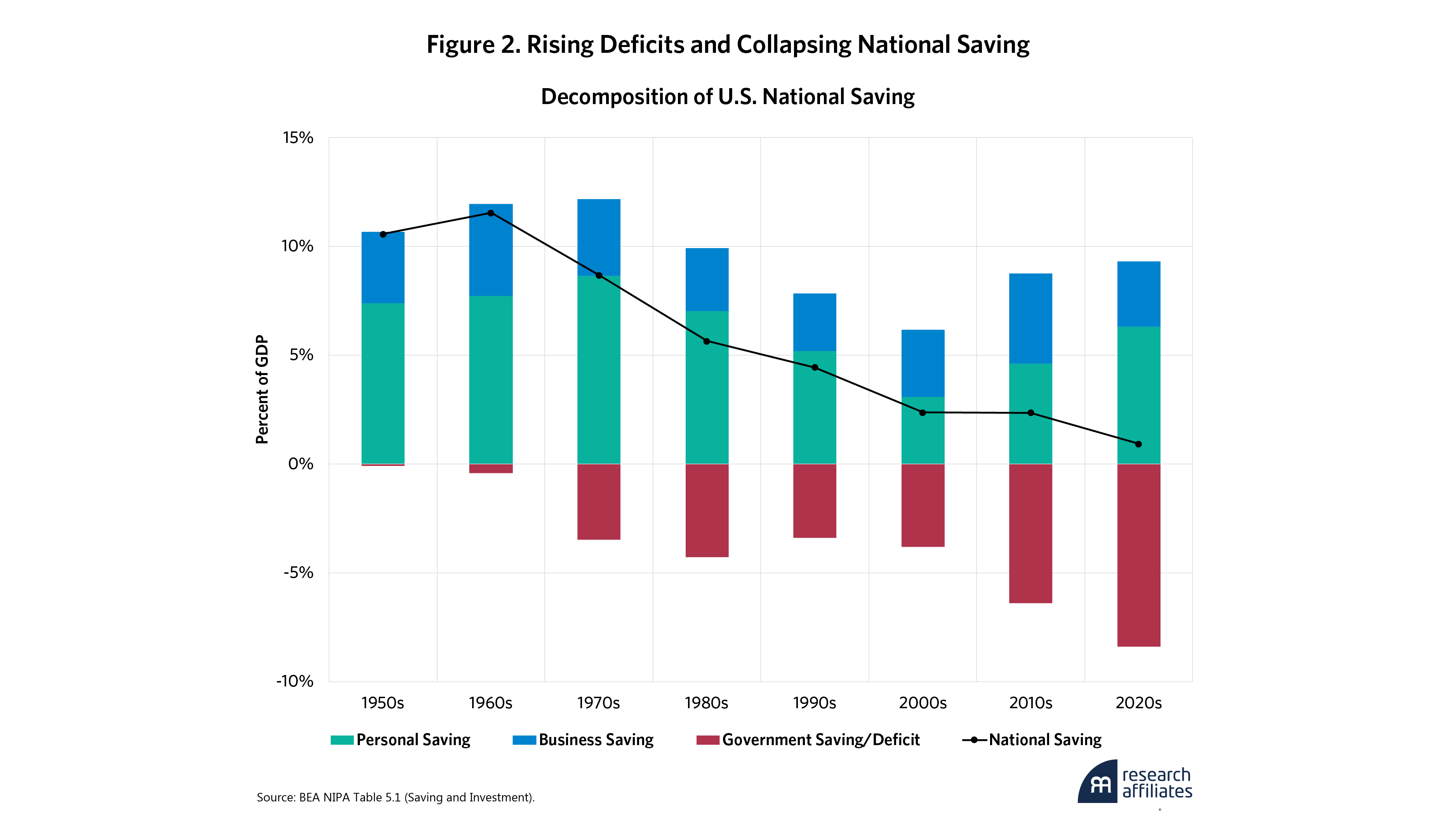

Fiscal policy changed the relationship between saving and investment. The long-run data bear this out. Seventy years ago, the economy rested on the twin pillars of fiscal discipline and robust national saving. In the 1950s and 1960s, net domestic investment, funded entirely by national saving, averaged 11% of GDP. But then structural fiscal deficits started to offset private saving. As displayed in Exhibit 2, as rising fiscal deficits increasingly offset private saving, national saving plunged to near zero today.

Suppression of Real Rates

Interest rates started their extended decline after the extreme monetary tightening that ended the Great Inflation of the 1970s and early 1980s. Since then, save for a brief pause during the late-1990s fiscal surpluses, expanding fiscal and trade deficits have flooded the private sector with financial assets, inflating corporate profits and asset prices.

After China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, its mercantilist, export-led growth model generated large trade surpluses that were funneled into U.S. financial assets, thus introducing an enormous structural demand for U.S. Treasuries. A second and more deliberate phase of rate suppression followed the 2008 financial crisis, when central banks cut policy rates to zero and expanded their balance sheets through quantitative easing (QE).

With such low borrowing costs, governments could expand deficits without displacing private gross investment. Normally, interest rates would rise in response to such heavy borrowing, thereby increasing the cost of capital and discouraging private investment. Instead, the “global savings glut” and sustained fiscal stimulus kept rates down.

The cheap cost of capital did not spur gross investment. Intense global competition, especially from China, diminished returns from U.S domestic production, while a declining labor share slowed growth in household demand. Together these forces reduced profitable opportunities for physical investment in the domestic economy. With their limited need for capital, private borrowers did not compete with government borrowers. Rather than expand capacity, firms returned profits to shareholders through dividends and buybacks (Lazonick, 2014). The flow of foreign saving, mostly from China, was the necessary counterpart to rising U.S. trade deficits. When the United States consumes more than it produces it also saves less than it invests. In exchange for the excess of goods and services the U.S. consumes, foreign economies accumulate U.S. financial assets, specifically the newly issued Treasuries. Such acquisition of financial assets does not add to U.S. productive capacity; it reinforces the financialization of the economy.

Shifting Composition of Investment

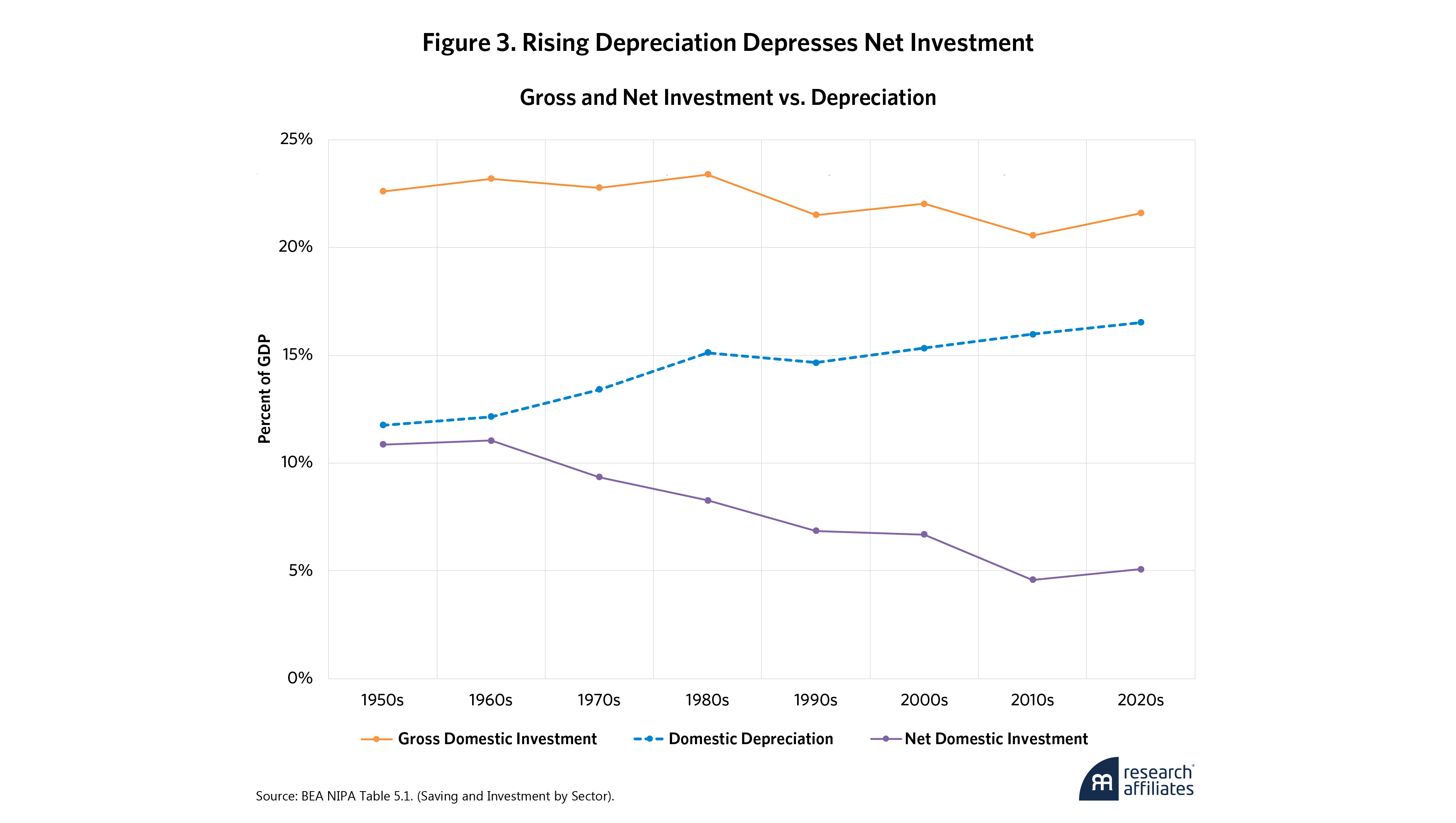

Fiscal policy appears to have caused national saving to collapse and crowded out net investment. Even though gross investment, as a share of GDP, remained more broadly stable, an increasing share of total investment now goes toward replacing depreciated capital rather than expanding capacity.

Gross domestic investment ebbs and flows with the business cycle, but its longer-term average has held relatively steady, only slipping from about 23% of GDP during the 1950s to 1980s to about 21% in recent decades. As Exhibit 3 shows, however, net domestic investment has declined from nearly 11% of GDP in the mid-twentieth century to about 5% in recent years. Over the same period, depreciation rose from roughly 12% of GDP to more than 16%.

Rising depreciation is due to the transition from an industrial base built on durable, tangible assets to a digital economy built on shorter-lived intangibles. The lifespans of digital capital assets are difficult to measure, but servers, software, data, and R&D wear out or become obsolete much faster than the factories, machinery, highways, and houses we built fifty years ago. The result is an economy that continues to invest, but mostly to maintain its existing capital stock rather than to expand its productive base.

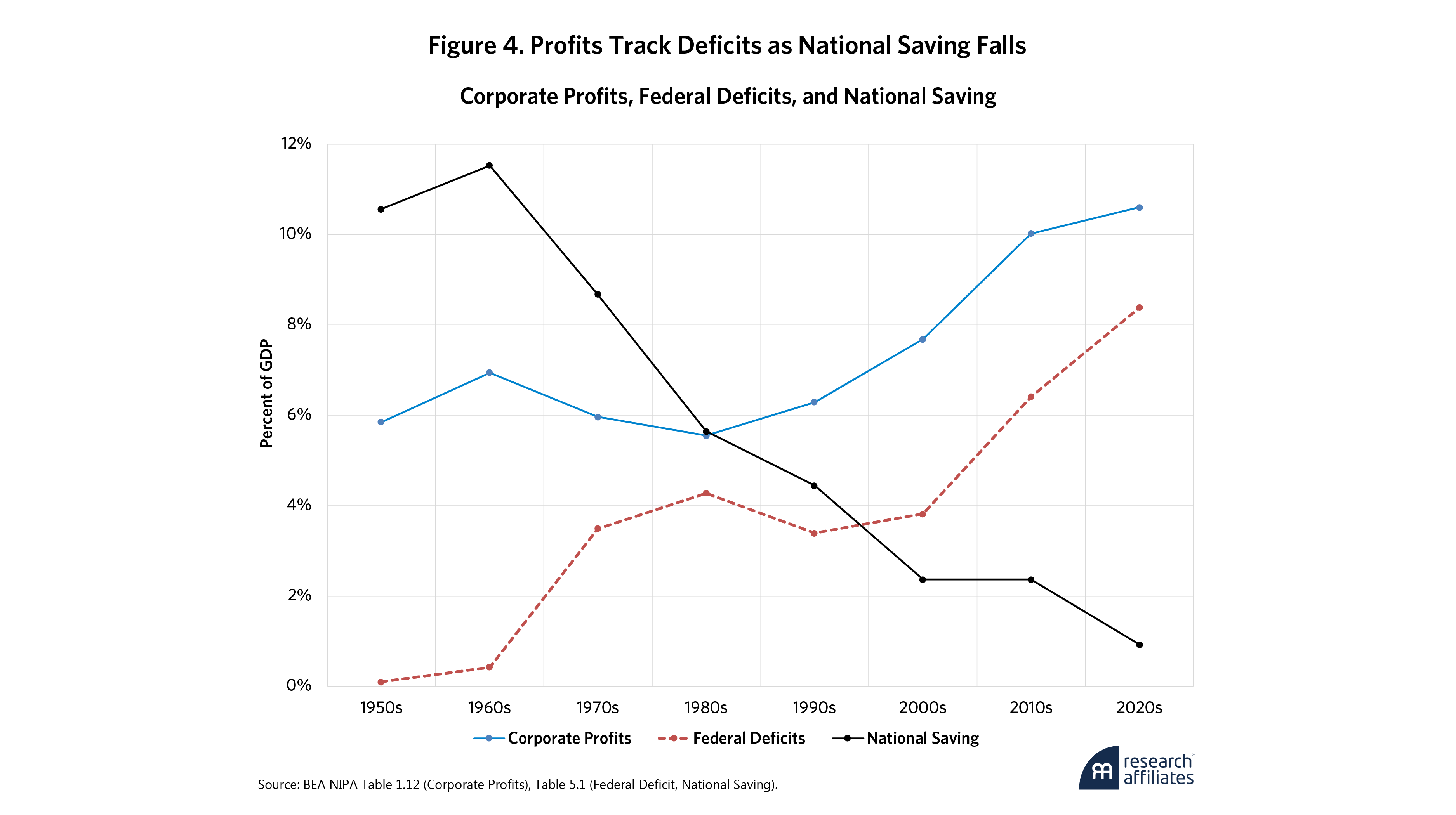

Financialization of Profits

Policy choices to fund rising entitlement spending through ongoing fiscal deficits inflated financial profits and stifled public investment. Because these deficits often occurred when the economy was already near full capacity, the extra spending increased consumption and profits rather than saving and investment.

Exhibit 4 shows how this financialization of profits affected historical trends. As deficits soared from near zero in the 1960s to 8% of GDP by the 2020s, the profit share grew in parallel, from 6% of GDP to more than 10%. Over this same time, national saving collapsed from 11% of GDP to near zero.

Financialization Contributed to Growing Inequality

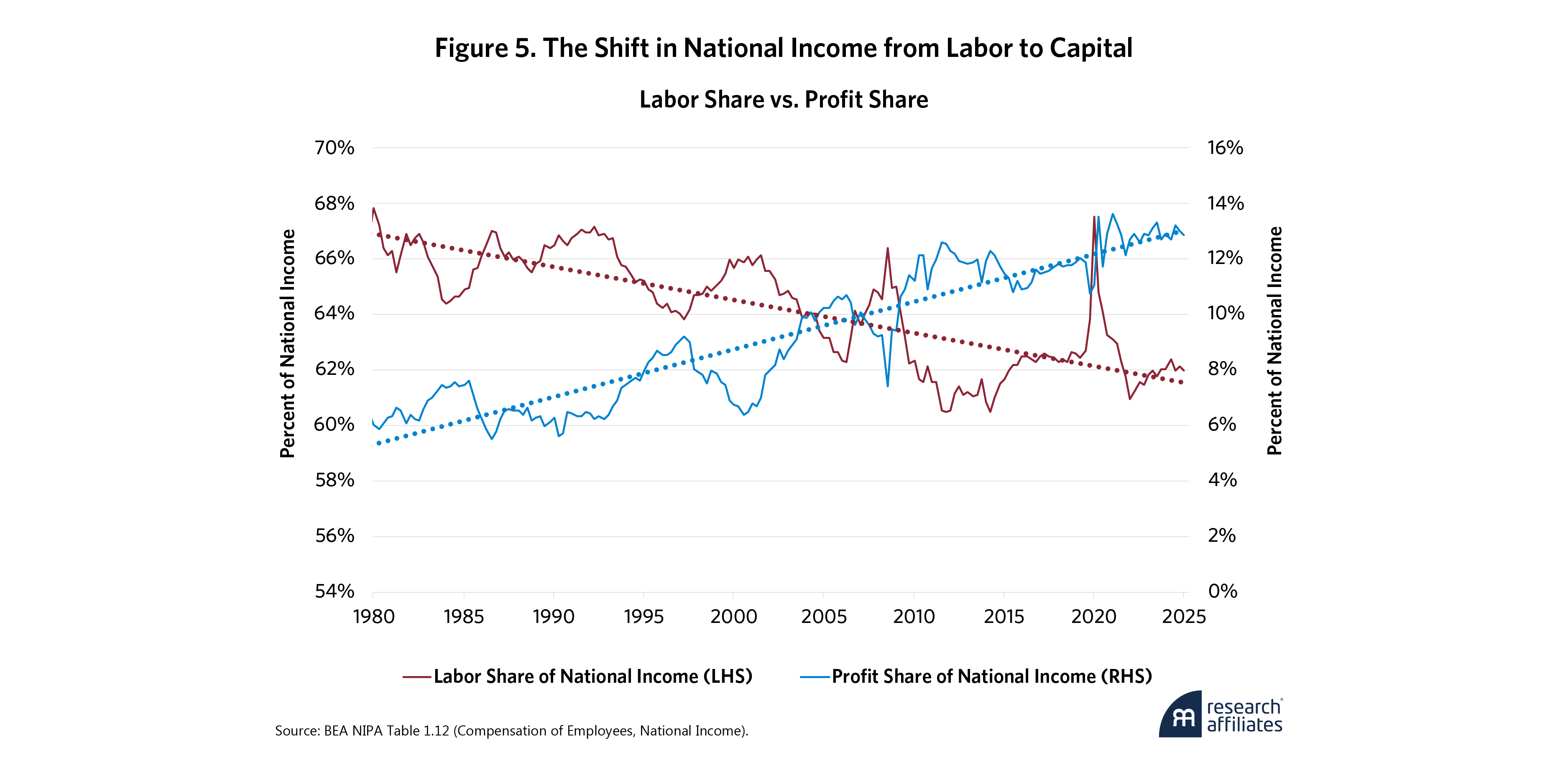

This growth in the profit share of GDP necessarily means a corresponding decline in the share of income accruing to labor and other factors of production. Exhibit 5 illustrates how national income shifted.

Even as social transfers soared by 10% as a percentage of GDP, the labor share of national income entered a prolonged decline, falling from near 68% in the early 1980s to 62% by the mid 2020s. Rising income from profits accrued to the wealthy and widened inequality. This shift has profound consequences for the financialization cycle.

As noted in the earlier section on profit distributions, profits accrue mainly to wealthy households, who spend little in the real economy and instead reinvest their income into financial assets. This recycling fuels the inelastic market mechanics that capitalize profit distributions into inflated valuations. The ongoing expansion of entitlement spending suggests this trend will continue.

Alternative Explanations

Several competing theories explain the rise in corporate profits, attributing the trend to increased monopoly power, globalization, and technological change, for example. The “superstar firm” hypothesis (Autor et al., 2020) proposes that with rising industry concentration, dominant firms extract higher profits. Jaumotte and Tytell, (2007) suggest that global labor arbitrage has suppressed wages, shifting income from labor to capital. Haskel and Westlake (2017) believe the emergence of high-margin, capital-light software and tech companies has boosted aggregate profit margins.

While valid and important, these factors operate within the larger macroeconomic environment established by fiscal and monetary policy. Chronic deficits inject aggregate income that flows into profits at the national level. These alternative theories help explain the distribution of profits among firms, but our model demonstrates the macroeconomic mechanics influencing the aggregate level of those profits.

Furthermore, while the demand-side channel of deficit-funded consumption is our primary focus, fiscal policy has also inflated profits on the supply side. As Smolyansky (2023) and others have shown, lower corporate tax rates and reduced interest expenses contribute to the deficit and boost corporate bottom lines. These mechanisms are complementary and demonstrate that fiscal policy has propped up corporate profitability from multiple directions.

A Fragile Stock Market

The foundation supporting U.S. corporate profits and equity valuations has weakened, leaving the market increasingly fragile. Profits now depend on large-scale fiscal deficits, a sharp departure from the mid-century model when profits were generated by private investment of retained earnings.

Reversion to a healthier macroeconomic environment of declining deficit spending and greater net investment may cause sharp declines in both corporate profits and valuation multiples and likely trigger a financial crisis with politically toxic consequences. Ironically, the more palatable option may be to remain on the current path until a financial crisis imposes on us the discipline that we are unwilling to impose on ourselves.

Please read our disclosures concurrent with this publication: https://www.researchaffiliates.com/legal/disclosures#investment-adviser-disclosure-and-disclaimers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rob Arnott, Brad Cornell, Campbell Harvey and Charles DuBois for their insightful comments and helpful suggestions. Any remaining errors or misinterpretations are our own.

Appendix Data Sources

The sources that helped guide the empirical analysis in this paper include the following:

BEA NIPA Tables:

- Table 1.12. National Income by Type of Income

- Table 1.1.5. Gross Domestic Product

- Table 3.12. Government Social Benefits

- Table 5.1. Saving and Investment by Sector

End Notes

1. We focus exclusively on the U.S. economy, where the dollar's reserve currency status provides a unique capacity to fund sustained deficits. We examine five decades of rising deficits, the capital share of GDP, and valuation of the stock market. Explanations of more recent growth in profits and potential overvaluation of some stocks, while consistent with this paper, is not the subject.

References

Autor, David, David Dorn, Lawrence F. Katz, Christina Patterson, and John Van Reenen. 2020. “The Fall of the Labor Share and the Rise of Superstar Firms.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 135 (2): 645–709.

Ben-Rephael, Avi, Shmuel Kandel, and Avi Wohl. 2012. “The Price Pressure of Aggregate Mutual Fund Flows.” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 46 (2): 585–603.

Brightman, Chris, and Campbell R. Harvey. 2025. “Passive Aggressive: The Risks of Passive Investing Dominance.” SSRN.

Brightman, Chris, and Alex Pickard. 2025. “Financialization: How Fiscal Policy Has Inflated Profits and Equity Valuations” SSRN.

Gabaix, Xavier, and Ralph S. J. Koijen. 2021. “In Search of the Origins of Financial Fluctuations: The Inelastic Markets Hypothesis.” NBER Working Paper No. 28967.

Haskel, Jonathan, and Stian Westlake. 2017. “Capitalism Without Capital: The Rise of the Intangible Economy.” Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jaumotte, Florence, and Irina Tytell. 2007. “How Has the Globalization of Labor Affected the Labor Income Share in Advanced Countries?” IMF Working Paper No. 7/298.

Kalecki, Michal. 1942. “A Theory of Profits.” The Economic Journal 52 (206/207): 258–267.

Lazonick, William. 2014. “Profits Without Prosperity.” Harvard Business Review 92 (9): 46–55.

Levy, David A. 2012. “The Profits Perspective Explained.” Jerome Levy Forecasting Center.