Asset classes are often declared irretrievably broken after poor recent performance, implying they are unable to provide reasonable forward-looking returns. These proclamations are often nowcasts, a common and dangerous financial practice of explaining what’s already happened as if it’s a forecast of the future.

We survey (admittedly) anecdotal examples of so-called broken asset classes. In most cases, their performance fell within their historical range of expected returns. Further, following this declaration they often produced sizeable excess returns.

We offer practical tips for advisor conversations with clients about underperforming asset classes and their role in a portfolio.

Introduction

Pundits, prognosticators, and even investment boards often make misleading declarations that an asset class is broken, that its prospects for earning investors a reasonable future return are very dim. These proclamations can lead to investors’ abandoning these assets to chase recent winners. Advisors are uniquely positioned to educate their clients about historical asset-class returns and provide context for recent, perhaps disappointing, performance. In this way advisors can prepare their clients for substantial variations in an asset’s returns. A prepared client is a confident one. And confidence begets the tenacity to hold assets over the long term, raising the likelihood of a successful investment experience via diversification, rebalancing, and long-term compounding. And isn’t that what financial advice is all about?

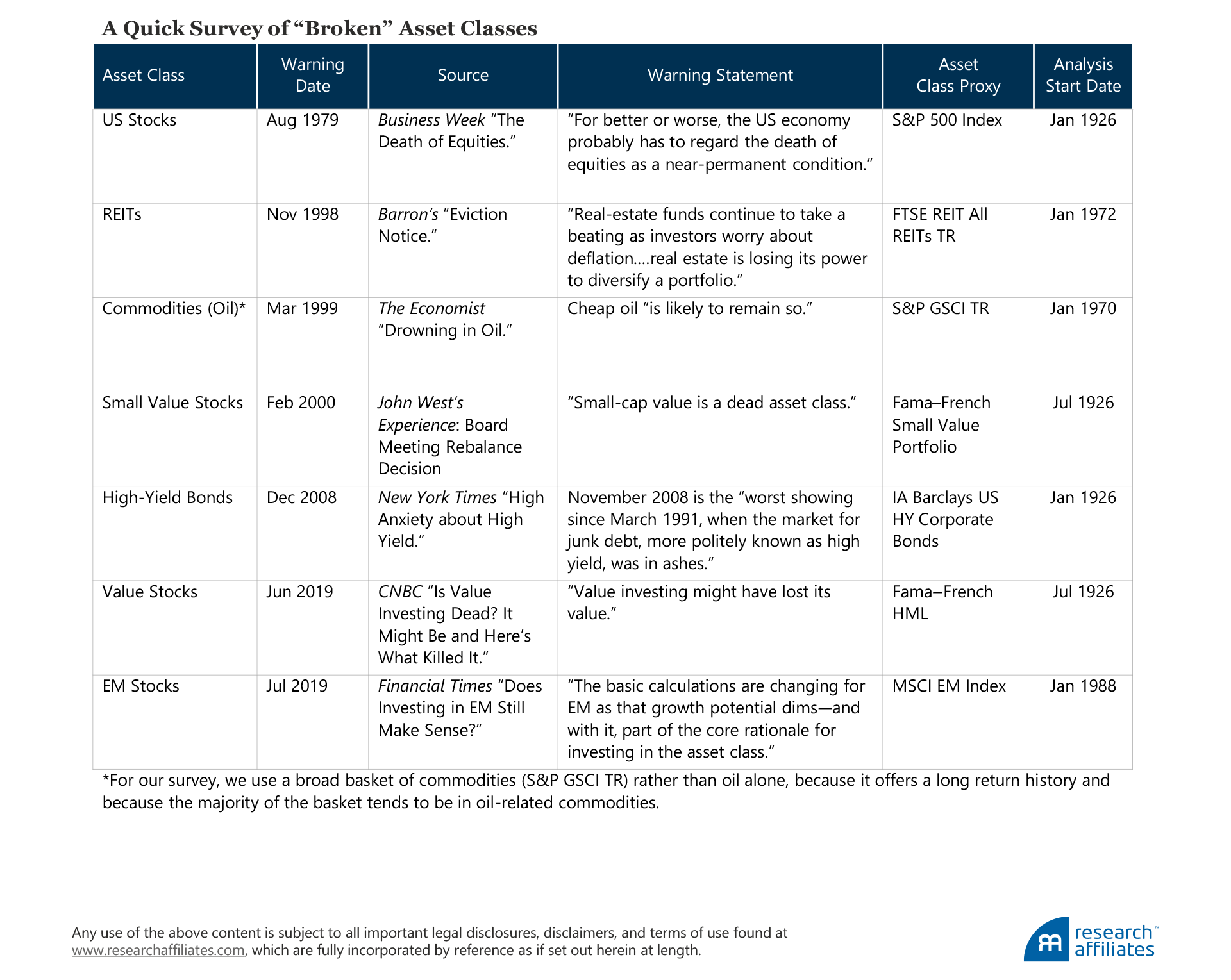

Warnings of the long-term impaired viability of asset classes have spooked investors through history. One of the most notorious was Business Week’s cover story “The Death of Equities” published in 1979. US stocks are not alone however; other “broken” asset classes abound. By the late 1990s, REITs were dismissed as “losing [the] power to diversify a portfolio” (Henderson, 1998), and a 1999 article in The Economist concluded cheap oil “is likely to remain so.” Fast-forward 20 years to the present. Headlines teem with sentiments such as “Does Investing in Emerging Markets Still Make Sense?” (Wheatley, 2019) and “Is Value Investing Dead? It Might Be and Here’s What Killed It” (Li, 2019).1

History is littered with examples of reputable pundits, media outlets, and prognosticators cautioning investors about broken asset classes, typically at the heels of sagging absolute returns or poor results relative to mainstream markets. Similar warnings also occur during investment board meetings. In his consulting days, John recalls, back in February 2000, a board meeting of an $800 million pension fund. Recent market movements (namely, growth stock outperformance) had pushed the fund’s asset allocation out of compliance with its investment policy statement, requiring a large rebalance out of growth stocks into core bonds and small-cap value.

The resistance to the mandated rebalance was unsurprisingly (for those who may have lived through this period) stiff, with one board member stating that “small-cap value is a dead asset class.” Indeed, it appeared the board preferred to eliminate small-cap value rather than top it up. Fortunately, the investment policy statement compelled the rebalance to go through. To this day, John will tell you it was one of his most rewarding experiences in investment management given the absolute dollar value created for the fund’s members as growth stocks plunged, small value stocks surged, and bonds steadily advanced during the bear market that eventually culminated in late 2002.

When headlines lead to clients’ questioning their investment strategy, we suggest advisors use comprehensive historical return ranges to most effectively gauge recent results on an absolute basis and relative to a mainstream asset such as US equities (i.e., the S&P 500 Index). We will review how seemingly impaired assets are rarely permanently defunct. In most cases, the performance of a broken asset class is well within its range of historical returns, and outperformance often follows a period of underperformance as mean reversion takes hold. Clients benefit from a greater understanding of the potential long-term upside in recently beaten-down assets.

The Broken Asset Classes

Before delving into our review, let’s begin with a few caveats. First, our selection of broken asset classes is far from exhaustive.2 In making our selection, we relied primarily on a global roster of historical articles published in the well-established financial press, including Business Week, Barron’s, The Economist, and Financial Times.3 If your own experience includes other asset classes that have been declared broken, please let us know!

Second, the headlines or conversations that question the long-term viability of an asset class represent just one opinion or voice at that time. Alongside those who warn and question, others may have presented an opposite, more favorable view. Contrarians are often an endangered species, but rarely extinct! Given that our survey’s purpose is to show how broken asset classes typically mend themselves with time, our sample emphasizes the former. These are the same troubled asset classes that grab the headlines, grip the attention of investors, and lead to tough questions for advisors from their clients.4

Finally, we are restricted by the availability of return data. Although we use well-known proxies with an extended return history, few asset classes other than US stocks and high-yield bonds have a monthly series longer than a half-century. A notable example is emerging market (EM) stocks. In our study, we use a return history for EM stocks that begins in 1985. A time span of just over 30 years is a relatively short time in the capital markets, and while results may not be statistically significant, they can be economically meaningful.

Ultimately, our survey includes seven asset classes, beginning with US stocks following the infamous “Death of Equities” article published in August 1979 and ending with a similar chorus of claims surrounding value investing and EM stocks 40 years later. And for good measure, we throw in John’s experience at the aforementioned board meeting.

What Constitutes “Broken”?

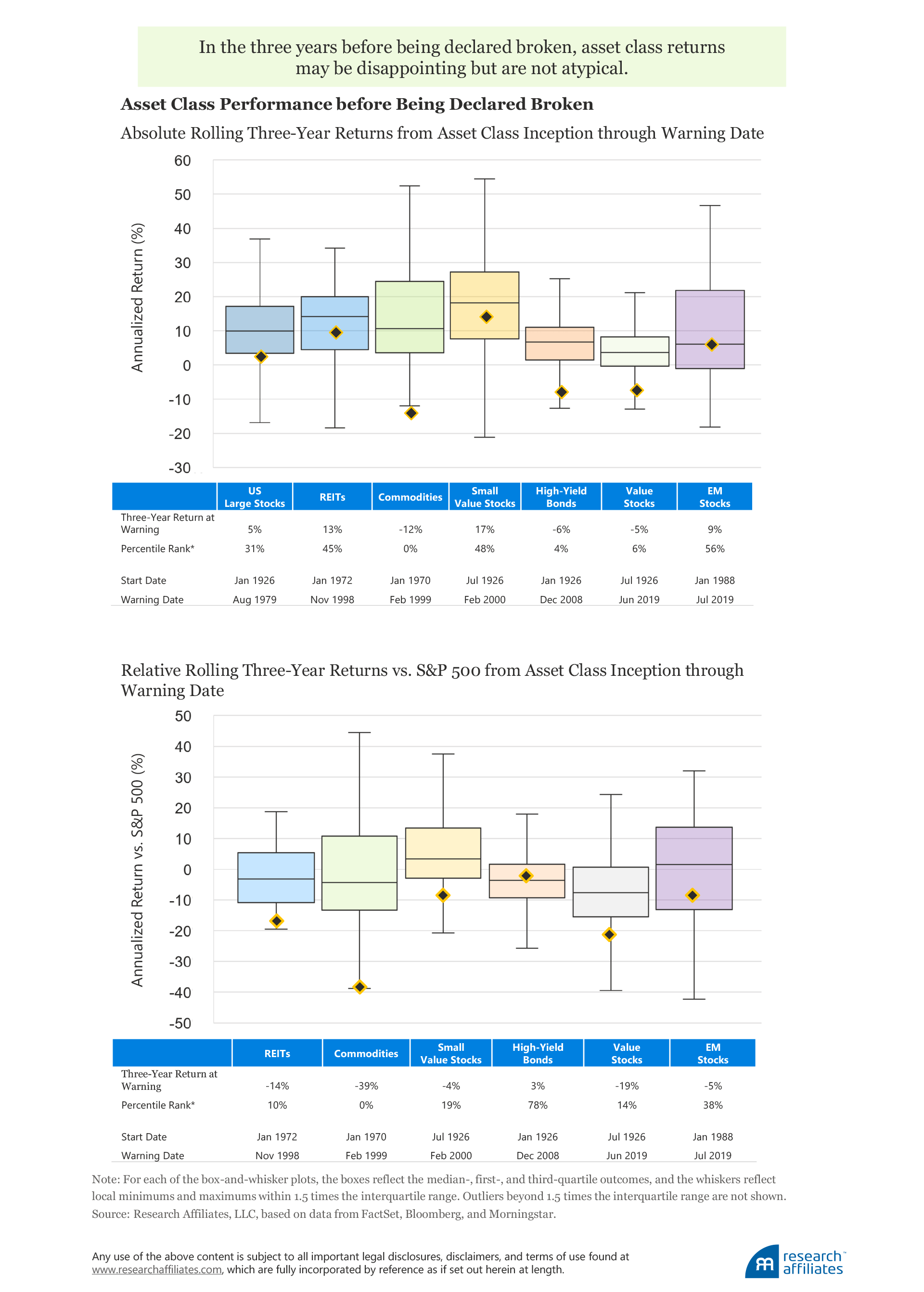

All seven of the broken asset classes in our survey posted poor performance over the three years prior to the warnings that they were impaired. Before we declare them broken, however, let’s take a look at their performance in the context of each asset’s long-term history—both in absolute terms and relative to mainstream US stocks. The warning date we use represents the month in which a published article or live conversation strongly questioned the long-term viability of the asset class.

Three-year performance results leading up to the warning date generally hovered near the lower ranges of long-term outcomes. At the time of the August 1979 warning about US stocks, their uninspired 5% annualized three-year return had slumped into the bottom quartile of returns since 1926. Approximately half of the group—commodities, high-yield bonds, and value stocks—generated negative returns that fell within the worst decile of each asset’s long-term historical three-year rolling return. These are disappointing, infrequent outcomes, but not atypical or improbable.

Broadly, performance results relative to the S&P 500 tended to be more severe than absolute outcomes, suggesting that anchoring on mainstream assets is pervasive. For instance, three asset classes—REITs, small value stocks, and EM stocks—managed to deliver returns slightly above their long-term median levels in the three years preceding the declarations' warning that they were defunct. But when viewed relative to mainstream assets, all three suffered relative shortfalls, trailing US stocks by up to 14% a year over the three-year period preceding their respective warning dates. They are not alone.

Every asset class in our subset, except for one,5 trailed the S&P 500 in the three years leading up to the warning date. The three-year relative losses of four of the five stragglers fell into the worst quintile of all historical outcomes—with two in the bottom decile. So, despite alarming warnings of the impaired viability of asset classes, the performance of broken asset classes is not particularly exceptional, generally falling within the normal, albeit bottom, range of return outcomes.

Mean Reversion and Missed Opportunities

Far too many investors focus on the rearview mirror and react to fear-inducing headlines. Doing so incurs the risk that investors will miss good opportunities. Markets are supposed to pay a risk (or “fear”) premium to reward risk bearing. Perception of risk and fear tend to go hand in hand. Asset classes get sold down to bargain levels because people are fearful. As our colleague Rob Arnott regularly says, “when risks and bad news are known to the market and fear is prevalent, it’s time to buy what’s out of favor, unloved, and legitimately creating fear.” Fear-based anomalies persist because their genesis is in humans’ primal impulses.

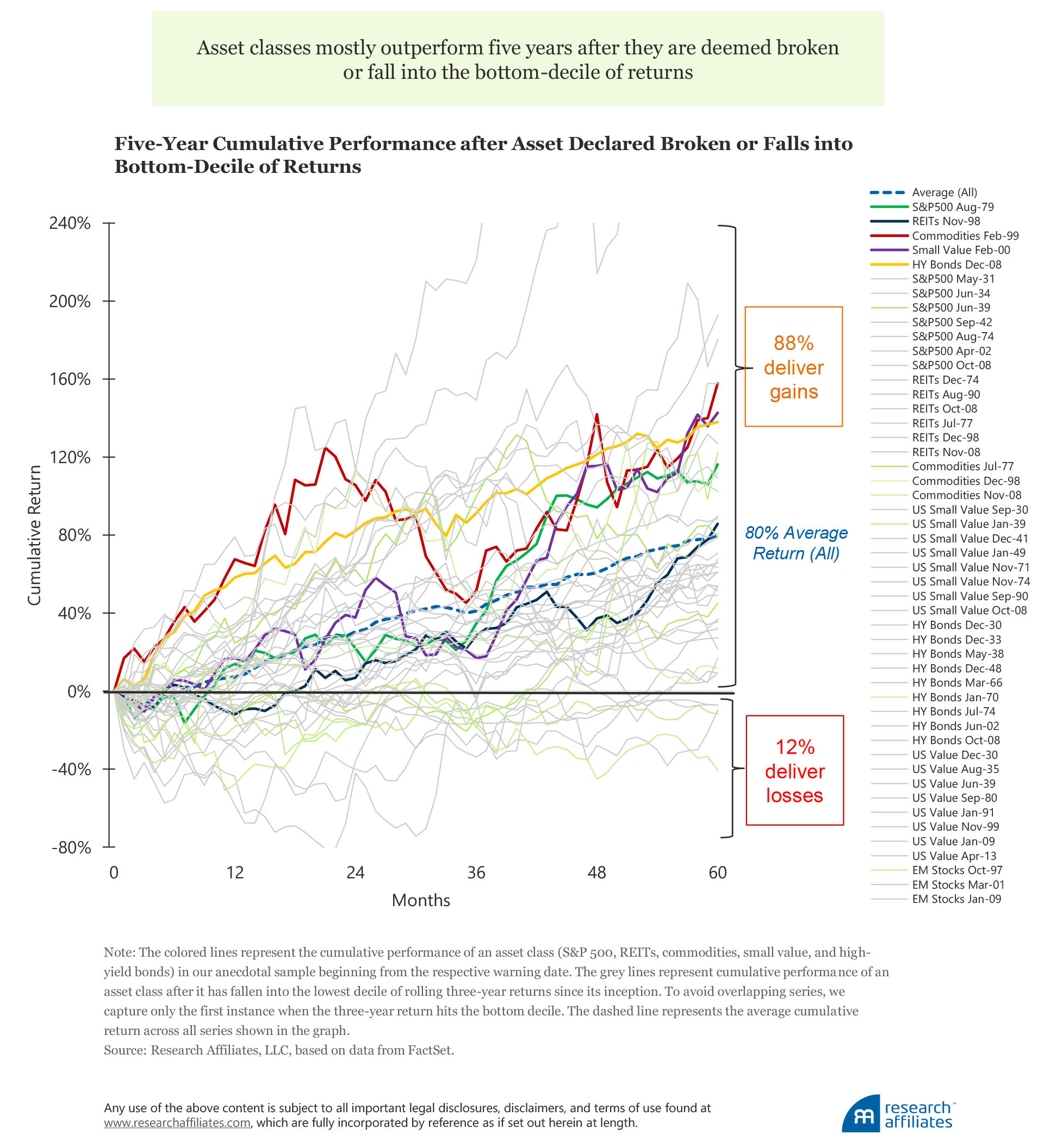

In the five years after an asset class was declared broken, each roared back in a strong, and for many, swift rebound. All except one snapped back within one year, generating returns that ranged from 14% for US stocks to 68% for commodities. The sole dawdler, REITs, rebounded in 18 months, ultimately delivering a cumulative 86% return at the five-year mark—the weakest performance of the group.

We recognize the substantial survivorship bias in our survey, having personally survived most of these episodes ourselves! So, to be more comprehensive, we also plot other periods when these asset classes fell within their lowest decile of historical three-year rolling absolute returns.6 A similar pattern unfolds. A large majority, or 88%, of all observations (43 of 49) deliver a positive five-year return. The average five-year cumulative return across all observations is 80%, or approximately 12% a year, suggesting both the presence and strength of mean reversion.

How do the asset classes perform on a relative basis? Recall that the broken asset classes in our survey had mostly fallen short of the performance of the S&P 500 in the years leading up to the proclamation they were broken. In the subsequent three years, these asset classes surpassed the performance of US stocks on a cumulative basis by an average of 45%, or 13% a year. After five years, the cumulative excess return of REITS, commodities, small value stocks, and high-yield bonds versus the S&P 500 averaged 101%, or 15% a year. Over this five-year span, the four asset classes fared significantly better than US stocks, with cumulative excess returns ranging from 10% (high-yield bonds) to 158% (commodities).

The press is often quick to label asset classes broken. Rarely is this the case, although exceptions do exist. For instance, the German and Russian stock markets during World War I, Japanese and German stock markets during World War II, and the Egyptian stock market in the early 1950s all collapsed. The near-obliteration of a stock market has happened, but it is an extraordinary occurrence.

The Advisor’s Role

We are hard-wired to pay attention to headlines with fear-provoking warnings. It’s easy to fall prey to nowcasts and believe that what’s already happened is a forecast of more of the same. While such predictions may sound cogent, they rarely offer insight. Our simple survey of broken asset classes reveals the following observations:

- Warnings of the impaired viability of asset classes tend to be exaggerated. The three-year performance leading up to the time that an asset class is pronounced irretrievably broken is typically within the normal, albeit wide, range of historical return outcomes.

- Returns are time varying and rebounds can be strong. After assets are either declared broken or decline to their lowest historical decile of three-year outcomes, the majority (90%) rebound within five years. The recovery also tends to be meaningful: the average cumulative five-year subsequent return across all observations is 80%, or 12% a year.

Our primary point is not to conclusively say that bottom-decile performance will be succeeded by brilliant subsequent returns. Our survey is not comprehensive. Even if it was, the future will not exactly mimic the past. Rather, our intent is to highlight how the advisor is uniquely positioned to prepare clients for the wide range of absolute and relative returns that capital markets will inevitably throw at them.

In most cases, parroting Mark Twain, reports of asset-class deaths are greatly exaggerated. But sadly these misleading proclamations can lead to investors’ abandoning these assets to chase recent winners. These types of poor investment decisions can be prevented, however, with proper preparation, such as educating clients about historical asset-class returns to provide context for recent, perhaps disappointing, performance. This is particularly important with diversifying assets as compared to the more-traditional asset classes of stocks and investment-grade bonds. By definition, the role of diversifiers, such as high-yield bonds and commodities, is not to mimic mainstream markets like the S&P 500!

Actor Richard Kline once said, “Confidence is preparation. Everything else is beyond your control.” The past 12 weeks of market tumult has certainly taught us that returns are well outside of our control. But an advisor can prepare their clients for substantial variations in an asset’s returns and obtain buy-in for these wide and ultimately unknowable ranges. A prepared client is a confident one. And confidence begets long-termism. And long-termism helps tune out the noise and raises the likelihood of a successful investment experience via diversification, rebalancing, and long-term compounding. And isn’t that what financial advice is all about?

Please read our disclosures concurrent with this publication: https://www.researchaffiliates.com/legal/disclosures#investment-adviser-disclosure-and-disclaimers.

Endnotes

- Our colleagues conducted a recent study of value stocks and published their findings in “Reports of Value’s Death May Be Greatly Exaggerated" (Arnott et al., 2020). Their findings suggest that value's performance shortfall relative to growth comes from value becoming less and less expensive compared to growth measured by valuation multiples, rather than because value stocks have experienced unprecedented headwinds or because growth opportunities for value stocks are abnormally poor relative to the past. In addition, Brightman, Mazzoleni, and Treussard (2018) offered a succinct summary of our views and assessment of the risk of a funding crisis in emerging markets.

- Our sample largely consists of commonly agreed-upon asset classes such as, for example, US stocks, EM stocks, high-yield bonds, and REITs. We recognize, however, that not everyone defines an asset class in the same way; for instance, whether value stocks or an individual equity sector or country should be classified as a distinct asset class is arguable. In general, we use the following criteria in specifying an asset class: 1) assets included in the asset class should be relatively homogeneous, 2) asset classes should be mutually exclusive, 3) asset classes should be diversifying, 4) asset classes as a group should compose a preponderance of world investable wealth, and 5) an asset class should have the capacity to absorb a significant fraction of an investor’s portfolio without seriously affecting the portfolio’s liquidity.

- Along with historical financial press headlines, we also rely on John West’s experience and conversation at Wurts & Associates (now Verus Advisory), for one of the cases (small value stocks).

- Psychological studies show that negative news tends to draw more attention than positive stories. Known as the negativity bias, people register negative stimuli more readily and ascribe more importance to them relative to positive stimuli. Because humans have evolved to react to potential threats, we have a stronger collective memory and faster response rate to negative events.

- The only asset class to outperform (by 3% a year) the S&P 500 was high-yield bonds. Note that despite a positive excess return over the three-year period ending December 2008, high-yield bonds’ absolute return, when viewed against the asset class’s own history, was woeful, falling into its worst 4th percentile.

- We study the first instance when the rolling three-year return hits its bottom decile and we avoid overlapping periods.

References

Arnott, Rob, Campbell Harvey, Vitali Kalesnik, and Juhani Linnainmaa. 2020. “Reports of Value’s Death May Be Greatly Exaggerated.” Research Affiliates Publications (May).

Arnott, Rob, and Jonathan Treussard. 2020. “Forecasts or Nowcasts? What’s on the Horizon for the 2020s?" Research Affiliates Publications (January).

Brightman, Chris, Michele Mazzoleni, and Jonathan Treussard. 2018. “Pundits Predicting Panic in Emerging Markets.” Research Affiliates Publications (June).

Dealbook. 2008. “High Anxiety About High Yield.” The New York Times (December 4).

Economist, The. 1999. “Drowning in Oil.” (May 4).

Henderson, Barry. 1998. “Eviction Notice.” Barron’s (November 16).

Leadbetter, Brent, John West, and Amie Ko. 2018. “Rebalance or Rush Hour?” Research Affiliates Publications (August).

Li, Yun. 2019. “Is Value Investing Dead? It Might Be and Here’s What Killed It.” CNBC.com (June 23).

Masturzo, Jim, and Jonathan Treussard. 2017. “Building Portfolios: Diversification without the Heartburn.” Research Affiliates Publications (October).

Ritholtz, Barry. 1979. “The Death of Equities.” Business Week (August 13).

Wheatley, Jonathan. 2019. “Does Investing in EM Still Make Sense?” Financial Times (July 15).