Investment professionals can overdo performance measurement simply because technology makes it so easy and it seems a worthwhile task to constantly gauge if clients are on the path to meeting their long-term financial goals.

Too often, however, “doing something” based on short-term performance measurement can degrade the long-term performance potential of a portfolio by chasing recent winners.

If we must regularly assess performance, let’s focus on performance relative to expectation distributions, such as a strategy’s expected tracking error of returns relative to its benchmark.

Introduction

In the last installment of the advisor series, our colleagues discussed how financial advisors can better serve their clients by shifting their due diligence efforts to identifying more reliable product designs in smart beta. In this article, we discuss why the investment industry is so obsessed with short-term performance evaluation and how investors can steer clear of the pitfalls arising from measuring and chasing returns.

If you’ve been a regular reader of our article series dedicated to the concerns of advisors, we hope you’ve found our ideas helpful in finding new ways to maximize your clients’ chances of achieving their financial goals. We started with a model of return and risk expectations (check!), added adequate diversification (check!), and reviewed product design and implementation considerations (check!). Next, it seems natural to closely monitor how investments perform over time, right? Well, not so fast. Before we engage in the common practice of performance assessment, let’s take a deep breath and recognize that, in many cases, we’d be better off not engaging in regularly scheduled performance measurement. Of course, that’s much easier said than done. And since we almost certainly must measure performance, we recommend doing so within a framework that acknowledges short-term noise and encourages investors to stay the course as they pursue long-term investment returns that are less random and more predictable.

The Things We Do

Most investment professionals—financial advisors included—seem to devote nearly as much time to performance measurement on the job, as we humans seem to spend on social media, off the job, these days. Sadly, we appear to be doing far too much of both. In the case of performance measurement, technology simply makes it so easy to run the numbers.1 Keeping close tabs on portfolio performance must be “proof” we are acting as responsible fiduciaries and investors, and is a guide to us in making superior decisions. Unfortunately, the evidence suggests otherwise. Just because we can do something, and have been doing it often in the past, doesn't make it a worthwhile activity.2 Instead, we might all be better served by taking a step back from the endless noise and step off the treadmill of “doing” to ask ourselves a few questions: Why do we spend so much time as a profession measuring and comparing the recent performance of securities, managers, and investment styles? Does this practice add value over the long run?

I’ve taken the unconventional step of deleting my Facebook and Twitter accounts over the last year. I can’t say that I miss either. Now, I’m not advocating you should fully unplug and stop looking at performance. I’m simply reflecting what we believe at Research Affiliates: that investors need to recognize a) the large sunk costs that come from obsessively monitoring performance and b) the natural (and dangerous) consequences that emerge from this activity. Namely, costly mistakes arise when we react to short-term performance assessments by piling into the recently brilliantly performing strategies and selling the performance laggards. In short, traditional performance measurement can be far worse than a neutral time sink akin to playing Candy Crush. It can actually detract from a client’s realized returns when the activity of measuring performance turns into chasing performance. The natural human instinct of “Don’t just sit there, do something!” encourages us to favor investments that have done well recently and to pull away from recent poor performers—just when predictable long-run mean reversion lies ahead.

The Cost of Our Obsession

So, why do we spend so much time measuring and comparing the past performance of securities, managers, and investment styles? One likely reason is a common belief that looking at historical returns leads to better portfolio management and investment decisions for our clients. And to a certain extent, that belief is obviously backed by our own experience.

As we have noted earlier in the series, several sources of a long-term robust return premium exist, but let’s use value as an example here. Those who “believe in value” have the added comfort of the self-evident logic that prices matter in investing as they do in everyday life, aligning with the existence of very long return series that “confirm” this logic with data. From this perspective, looking at realized performance is helpful and, in fact, is the basis for applying a scientific approach to investing.

But problems arise when we outsource our lack of conviction in an investment, such as a factor or a style, to its time series. In the lingo of finance academics, this is the difference between having a Bayesian prior (and informing it further with available data) and not having a prior, whatsoever, on which to base educated investment decisions.3

Nonprofessional investors can be forgiven for taking this unfortunate shortcut. They do not have the knowledge base advisors do, which can lead them, understandably, to believe that the “proof is in the pudding” in terms of performance, as it is with many things in life. (To be clear, this observation is not a slight to nonprofessional investors—even the most skilled of experts can fall prey to behavioral fallacies and knowledge gaps.) Obviously, not everyone can, or should, be a professional investor. Job specialization is very necessary, as you and I likely have little desire to build our own car or perform our own surgery. But those of us who do make our living as well-trained and well-intentioned overseers of capital, including financial advisors, can and must recognize the dangers of short-term performance measurement.4 The most evident way to combat this peril is to develop investment beliefs informed by, but not solely derived from, data.5

The reality, however, is that performance measurement often leads us to now-cast—a combination of “now” and “forecast”—which presumes that the near-term future will look an awful lot like the near-term past. The human brain loves a good way to make sense of an uncertain future, and where better to look than in the readily available past. Blindly relying on recent performance to infer a lasting future trend is fraught with danger.

Is There More Than Just Noise?

Let’s illustrate this with an example and assume our client, Chaser Chad, has reasonable expectations of long-term return and risk along with a solid understanding of the benefits of diversification. He believes that value is a robust source of excess return, and thus a portion of his portfolio includes several different value-oriented equity strategies. Actively keeping tabs on his investments, Chaser Chad notices that over the last three years, one of his value strategies has outperformed another one in his portfolio by nearly 3.5% a year. Hence, he wishes to sell the underperforming strategy and move those funds to the brilliantly performing one. Chaser Chad is not alone: this thinking is pervasive in our industry. Granted, over a long time span, a wide performance differential between two seemingly similar strategies may signal differences in execution, fees, or costs. But over shorter periods, “noise”6 can be staggeringly attention grabbing, tantalizing investors to create stories and “reasons” to justify action.

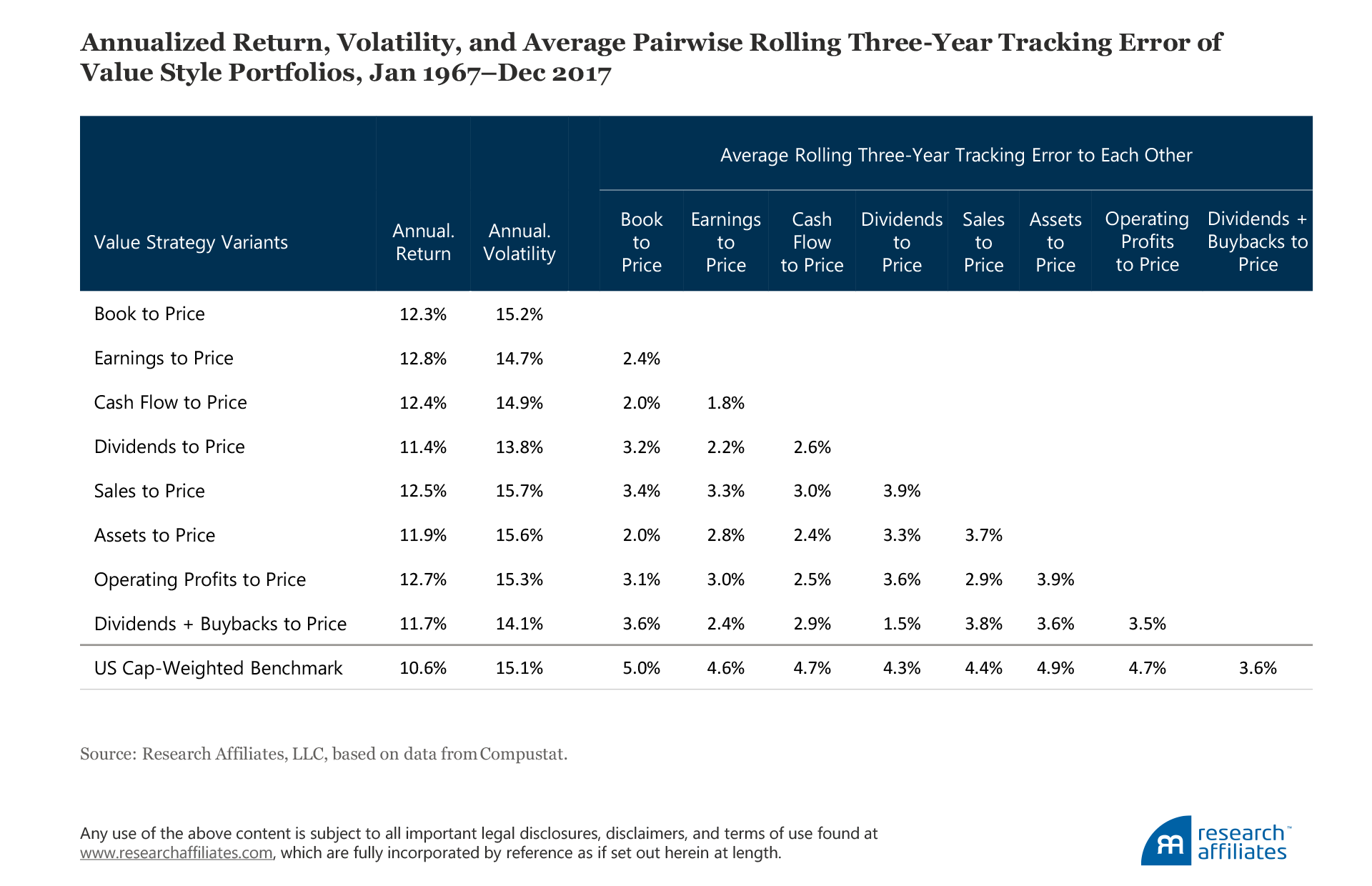

Consider eight hypothetical long-only value strategies, all using the sameconstruction method with just one variation, the value signal definition: book to price, earnings to price, cash-flow to price, dividends to price, sales to price, assets to price, operating profits to price, and dividends-plus-buybacks to price, respectively. Because they are all value strategies based on a priori equally valid metrics, our prior would be to expect them to deliver reasonably similar return outcomes over the long run. And yes, all generate an annualized return within a modestly narrow band of 11.4% to 12.8% over a 50-year period ending December 31, 2017.

When we begin to assess performance over shorter horizons, such as 3 years rather than 50, these nearly equivalent strategies from a 50-year perspective now appear to be extraordinarily different: their shorter-term returns deviate significantly. These performance differences are reflected in surprisingly high levels of three-year pairwise tracking errors to each another. From 1968 through 2017, the average rolling three-year pairwise tracking error was nearly 3%. In nearly one-fifth of the instances, the pairwise tracking error across these eight value strategies exceeded 4%. In the most extreme scenario, in the three-year period ending January 2001, two of the strategies—operating profits to price and dividends-plus-buybacks to price—exhibited a tracking error of returns to one another of nearly 9%. This wide variability in short-term performance is essentially noise and easily gives the illusion that an underlying reason explains the differential and that investors—especially the attentive, skilled, and opportunistic ones—have a chance to profit by gearing their long-term investments to the near-term evidence of superior returns.

A ranking of the eight strategies over each of the five-year horizons between 1968 and 2017 shows that none persistently remained as leader or laggard over subsequent five-year horizons. For example, a high-ranked strategy in the five-year window 1988–1992, the sales-to-price strategy, falls to bottom-ranked in the next five-year window, 1993–1997. The strategy then reverts to a top-ranked placement over the next two five-year windows. We see this pattern throughout; dividends-plus-buybacks to price is another example. My colleague John West is fond of saying that mean reversion is unreliably reliable, and we see here quite clearly that the process of mean reversion turns return-chasing behavior into a drag on investment outcomes.

Let’s Not Overdo It

The notion that everyone will delete their social media accounts is unrealistic—although I wonder what would happen if everyone did. Similarly, the notion that the investment industry will abandon short-term performance assessment is impractical. If we must regularly assess performance, let’s focus on performance relative to expectation distributions, such as a strategy’s tracking error of returns relative to its benchmark. By doing so, we are better able to short-circuit our behavioral tendencies and recognize that near-term performance is well within the range of reasonably expected deviations the vast majority of the time.7 From this perspective, we can conclude that investors are better off doing nothing much of the time, as opposed to doing something, assuming that we have positive priors for the strategies we are evaluating.8

The choice of “doing less” rather than more also has the distinct advantage of being a trading-cost-reducing strategy. As we de-emphasize the importance of short-term performance, we also gain an appreciation for the fact that long-term performance expectations have less noise built into them. Therefore, we can approach the task of assessing long-term performance with more confidence, though not certainty. Over longer horizons, such as a 10-year window, excess returns fall within a smaller range of outcomes, making performance measurement and managing to these measurements—thus bypassing the follies of return chasing (Arnott, Kalesnik, and Wu, 2017)—a more rewarding activity for advisors and their clients.

Endnotes

- Over 20 years ago, Bernstein (1995) alluded to the revolution in technology available for the task of performance measurement as he highlighted the proliferation of questionable bogeys (or benchmarks) by which investors gauge performance and underscored the fact that the difficulties in telling luck and skill apart make performance measurement a less-than-ideal pursuit. The reader will note I echo some of his themes in this article. Although I do not discuss benchmark selection, I refer the reader to Bernstein’s apt use of analogy in capturing the challenge of choosing the right bogey. Drawing a parallel between benchmark selection and congressional hearings during the McCarthy era, he reminds us of the line, “Who will investigate the man who’ll investigate the man who’ll investigate me?” We miss Peter Bernstein’s insights and writings.

- The evolution of computational and information technology has produced over the last few decades several obvious large-scale benefits for investors, beyond making performance measurement a simple task. First among them is the ability to scale up investment insights via quantitative methods. That being said, as discussed by Treussard and Arnott (2017), the dark side of this evolution in data processing has been the unleashing of careless backtesting, upon which live strategies are built. Again, replacing careful analysis and theory with mindless computation and data processing (aka outsourcing the hard work to the data) can easily lead quants astray.

- Duke Professor and Senior Advisor to Research Affiliates Cam Harvey makes this distinction very aptly in his 2017 Presidential Address to the American Finance Association (Harvey, 2017). Imagine that a musicologist correctly distinguished 10 out of 10 pages of music as being written either by Mozart or by Haydn. Also imagine that a kindergartener calls 10 coin flips correctly. Would you be as convinced of the child’s skills as you would be of the musicologist’s? I would hope the answer is “no” because you have a prior on the skills brought to the task, as opposed to being simple luck. Priors aren’t perfect (who knows, maybe the five-year-old is a budding fortune teller…), but they are very helpful.

- The presence of human capital in investment management should enable professionals to make better decisions relative to nonprofessionals because the professionals should have the necessary information on which to base decisions; that is, professionals should have conditional expectations that are refined relative to the unconditional expectations of lay people (Treussard, 2011).

- Brightman, Masturzo, and Treussard (2014) articulated Research Affiliates’ most foundational investment belief: Long-horizon mean reversion is the source of the largest and most persistent active investment opportunities.

- We encourage interested readers to spend time learning more about noise in the seminal work by Black (1986).

- Silver (2012) made the point (in a chapter titled “How to Drown in Three Feet of Water”) that it is critically important to communicate uncertainty by being explicit about the range of reasonable deviations around a point-estimate prediction. Otherwise, it is too easy for undue precision in forecasts to turn into “being wrong” nearly all the time and causing people to react to the resulting perception of incorrectness. But oddly, confidence intervals are rarely provided, presumably because it undermines the irrational desire to believe that experts are precisely right and that uncertainty can be managed. Silver quotes Jan Hatzius, chief economist at Goldman Sachs, who said: “Why do people not give confidence intervals? Because they’re embarrassed. I think that’s the reason. People are embarrassed.” If this is the case, investment professionals with fiduciary responsibilities must put aside embarrassment and be more explicit about what they can and cannot know.

- Another very sensible objective of performance analysis is investment-tilt analysis rather than pure performance measurement, in which we study the extent to which a strategy’s or manager’s performance can be explained by well-researched and easily attainable investment styles or factors, such as value, size, and the like. Investors are well advised not to pay “active”-level fees when styles and factors are accessible at a fraction of the cost, where active fees may be reserved for the portion of performance in excess of the factor-based returns.

References

Arnott, Robert, Vitali Kalesnik, and Lillian Wu. 2017. “The Folly of Hiring Winners and Firing Losers.” Research Affiliates Publications (September).

Bernstein, Peter. 1995. “Risk as a History of Ideas.” Financial Analysts Journal, vol. 51, no. 1 (January/February):7–11.

Black, Fischer. 1986. “Noise.” Journal of Finance, vol. 41, no. 3 (July):528–543.

Brightman, Chris, James Masturzo, and Jonathan Treussard. 2014. “Our Investment Beliefs.” Research Affiliates Publications (October).

Harvey, Campbell. 2017. “The Scientific Outlook in Financial Economics: Transcript of the Presidential Address and Presentation Slides.” Duke I&E Research Paper No. 2017-06 (January 7). Available at SSRN.

Silver, Nate. 2012. The Signal and the Noise. Penguin Books: New York, NY:194–195.

Treussard, Jonathan. 2011. “An Options Approach to the Valuation of Active Management.” Unpublished white paper.

Treussard, Jonathan, and Robert Arnott. 2017. “I Was Blind, But Now I See: Bubbles in Academe.” Research Affiliates Publications (June).