Although the Fed is unlikely to raise rates in June, the reprieve will probably be short-lived. Damage has been done, and the expected further hikes mean more damage. The recession we are imminently facing is self-inflicted.

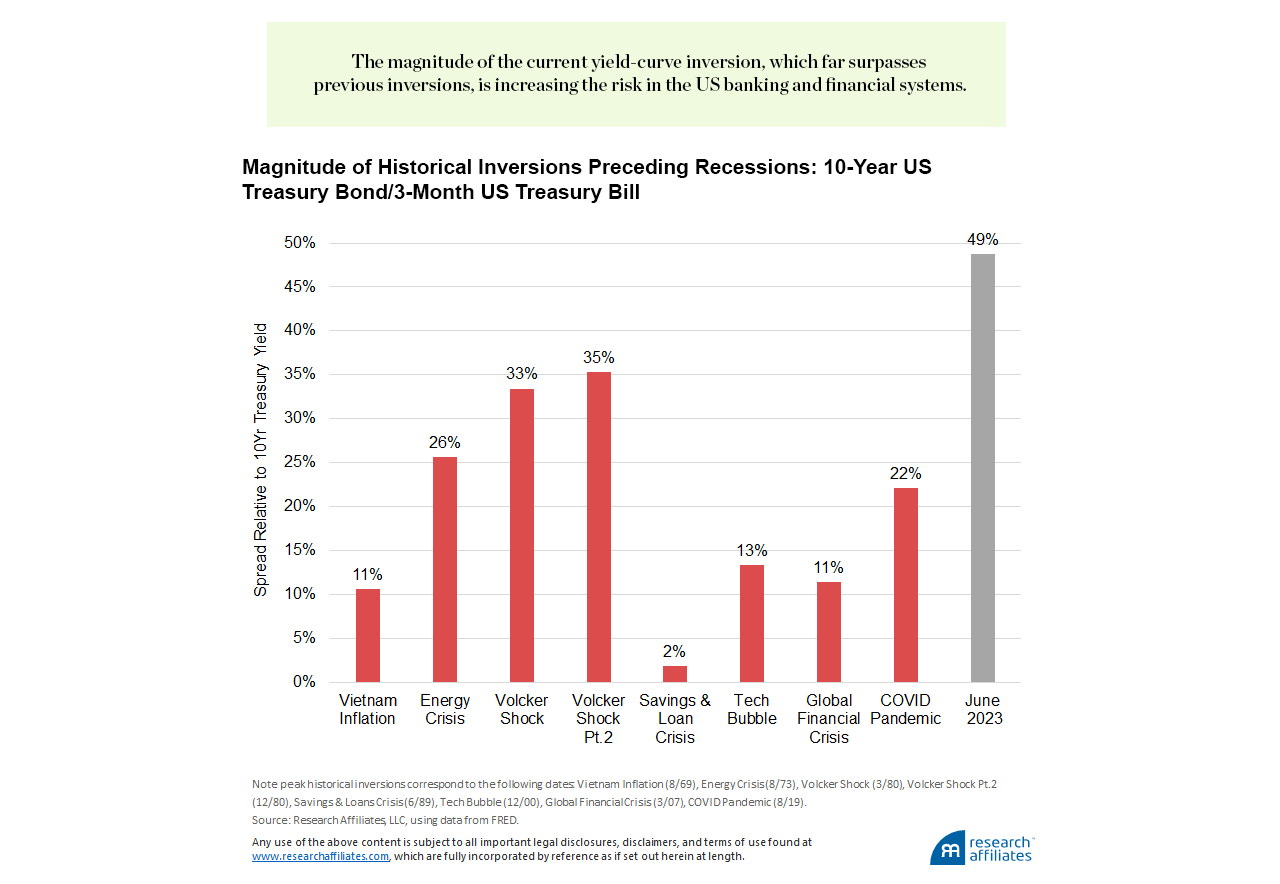

The inverted yield curve is responsible for two causal channels to this recession: 1) the self-fulfilling prophesy of its successful track record as a recessionary signal, and 2) the inversion’s magnitude, which is putting high levels of stress on the US banking and financial systems.

Two negatives—the Fed’s mistaken characterization of inflation as transitory, and the Fed’s failure to pause rate hikes in early 2023 amid signs of moderating inflation—do not make a positive. The result is a banking and financial system, as well as a commercial real estate market, under stress. As a result, the odds of a hard landing have increased.

Since January 4, 2023, I have argued that the Fed has been aggressively raising short rates to compensate for its earlier mistake of being late to realize that inflation was not temporary. Continuing to raise rates placed the Fed in danger of overshooting—increasing rates well beyond when it should have stopped—and jeopardizing the chance to achieve a soft landing. After the failures of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and two other large banks in the early spring, the Fed was in a lose–lose situation: a pause in rate hikes could be interpreted as a sign of a fragile banking system and lead to panic, whereas another hike would intensify stress on the financial system. On May 3, the Fed chose the latter option, hiking another 25 basis points (bps). That action and the previous hike heightened the likelihood of a hard-landing recession.

Create your free account or log in to keep reading.

Register or Log in

Likelihood of soft landing has given way to hard landing

In early January, even though my yield-curve indicator was flashing Code Red that a recession was imminent, I made the case that dodging the bullet was possible—the US economy could avoid a hard landing. Excess labor demand and stable consumer balance sheets indicated that realizing slow growth or minor negative growth was a feasible scenario. A recession, if it arrived, could be mild. The wildcard was the Fed.

The inverted yield curve—largely the Fed’s handiwork—opened the door to two causal channels to recession. One channel is the self-fulfilling prophesy of the successful track record of my inverted yield-curve signal (10-year Treasury bond yield minus three-month Treasury bill yield). With an eight-for-eight success rate in forecasting recessions since 1968 and no false signals, the current inversion is warning consumers and businesses alike to be cautious ahead of a likely recession. Saving more and postponing investment naturally leads to slower growth.

No CEO wants to stand before shareholders in late 2023 or early 2024 claiming they were blindsided by a recession. The inversion signal for recession is now too well known to overlook. Delaying capital investment and reducing head count as a precaution is simply prudent risk management. Although these moves would likely cause GDP growth to slow, the odds of a hard landing would be lower because companies would be leaner, having prepared for the slower growth. If the Fed had stopped hiking rates this year, this channel would probably have led to a soft landing or possibly no recession at all.

The second causal channel to recession is the major stress that the magnitude of the inversion (174 bps) is putting on the banking and financial systems. A positively sloped yield curve (long-term rates higher than short-term rates) is good for bank health, because banks generally pay short-term rates (for savings deposits) and receive longer-term rates (on their loan book and investments in longer-term government bonds). By aggressively raising short rates, the Fed has upended the normal model and created risk.

As a result, banks are struggling under an asset/liability mismatch. Because the Fed kept rates near zero during a period of robust economic growth, low unemployment, and record-high stock prices, banks and other institutions reached for yield and took on additional risk. The consequence is that they now hold portfolios of longer-duration bonds and loans that earn low rates of interest. The market rate banks must pay on their liabilities (customer deposits), however, is much higher. Additionally, banks’ longer-duration securities are trading at discounted values, the result of rising rates at the longer end of the yield curve. Liquidating these bonds to pay depositors who wish to withdraw their funds translates into bank losses.

The Fed’s refusal to pause rates through the first five months of 2023 sets up an unwanted scenario: a hard landing.

”Regulatory oversight and stress tests failed to identify or properly assess the duration risk that upended some of the banks. While we would like to believe that the banking crisis is behind us, how many other second-tier and regional banks are vulnerable to collapse? The stress in the financial system is causing uncertainty. We do not know the extent of the damage, but the Fed could alleviate much of the uncertainty in the market by providing to the public a data-driven analysis of bank risks. We would be able to answer the simple question: How many banks have negative equity right now? Three have failed and there are thousands of banks. Releasing such data to the market would inject some needed transparency and reduce uncertainty.

Two negatives do not make a positive

The Fed’s hesitancy in pausing rate hikes after its earlier mistake of waiting too long to begin raising rates does not equal a positive outcome for the US economy. In economics, two negatives make a bigger negative.

The Fed made a serious mistake viewing inflation as transitory and holding to that position for far too long. The data were showing us, even as we entered 2023, that inflation was moderating. Over the last 10 months, CPI has been running at an annualized rate of 3.3%, not the Fed’s 2.0% target, but close.

Shelter represents 33% of CPI and 40% of the Fed’s favorite inflation indicator, the Personal Consumption Expenditures deflator. The cost of shelter was the primary reason inflation began to rise in 2021. The Fed, surely aware that housing is a lagging indicator, should not have characterized inflation as transitory or made policy decisions that supported that view. Shelter-related costs are now trending down as both home prices and rents fall, but will take a while to work through the CPI. This trend was foreseeable in January. It is now June.

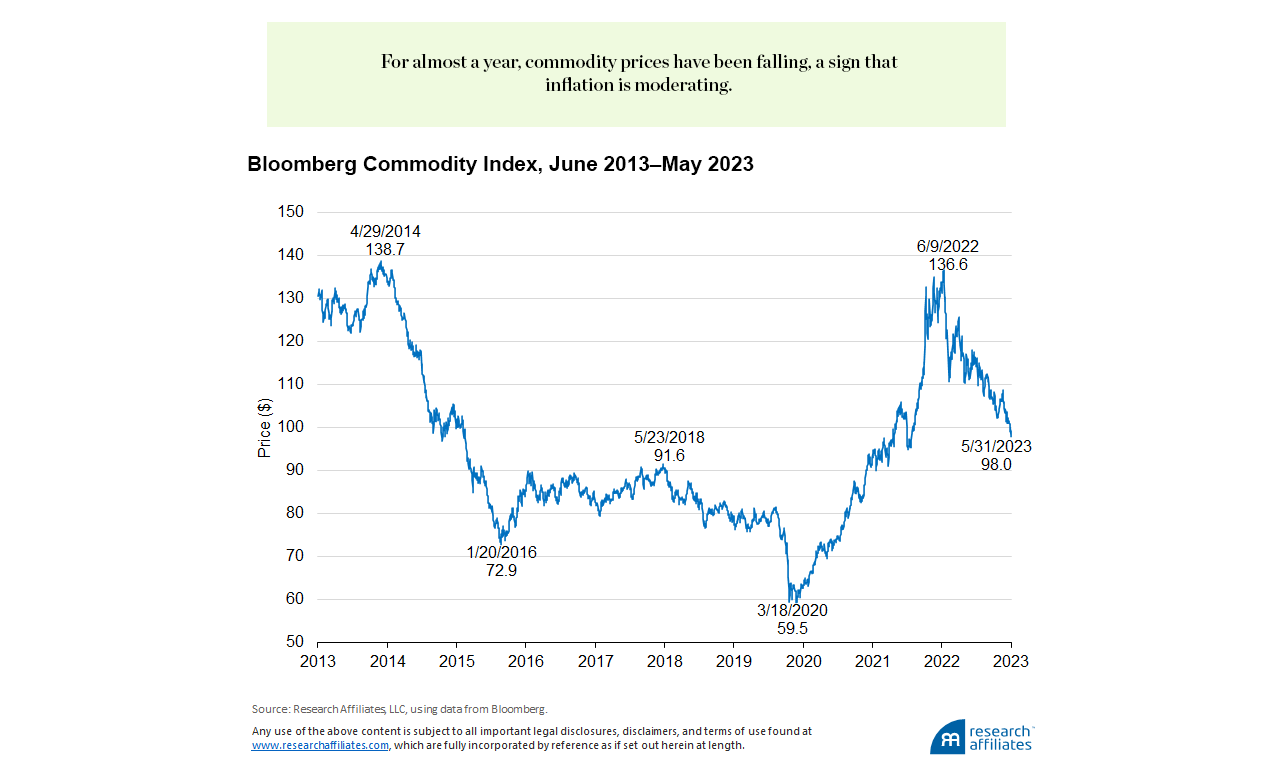

Another important inflation driver, commodity prices, has been trending down since June 2022. The Bloomberg Commodity Index is off 28.3% from its peak of nearly a year ago. This trend too was foreseeable in January. It is now June.

On the positive side, it does look like the Fed will not hike rates in June, but this will be six months too late. Further, a pause is not a cessation. It is widely expected the Fed will resume hikes later in the summer. I hope we can avoid a hard landing, but the Fed has (unnecessarily) made this outcome more likely.

Job numbers are strong, but remember that employment is a coincident or lagging indicator of economic growth. Unemployment is always low before recessions. That said, the excess demand for labor (job openings versus unemployed) is large and provides a potential buffer. In a hard landing, however, that buffer can vanish very quickly.

I see other areas of potential dysfunction in the banking and financial systems arising from the inverted yield curve. One is the potential zombification of parts of the banking system. According to the FDIC, the average interest rate paid on savings accounts is about 50 bps—and far lower at too-big-to-fail (TBTF) banks (I get 2 bps on a savings account at my TBTF bank)—while the average money-market-fund rate is over 450 bps. Why are the big banks not paying their depositors higher rates? Simply, because 50 bps is all they can afford given their asset/liability mismatch—and because they have the market power to do so. Depositors are already moving to money market funds; the risk of more bank stress seems obvious. Given the exodus from bank deposits, the implication is less money is available for corporate lending. Choking the credit channel will further decrease economic growth.

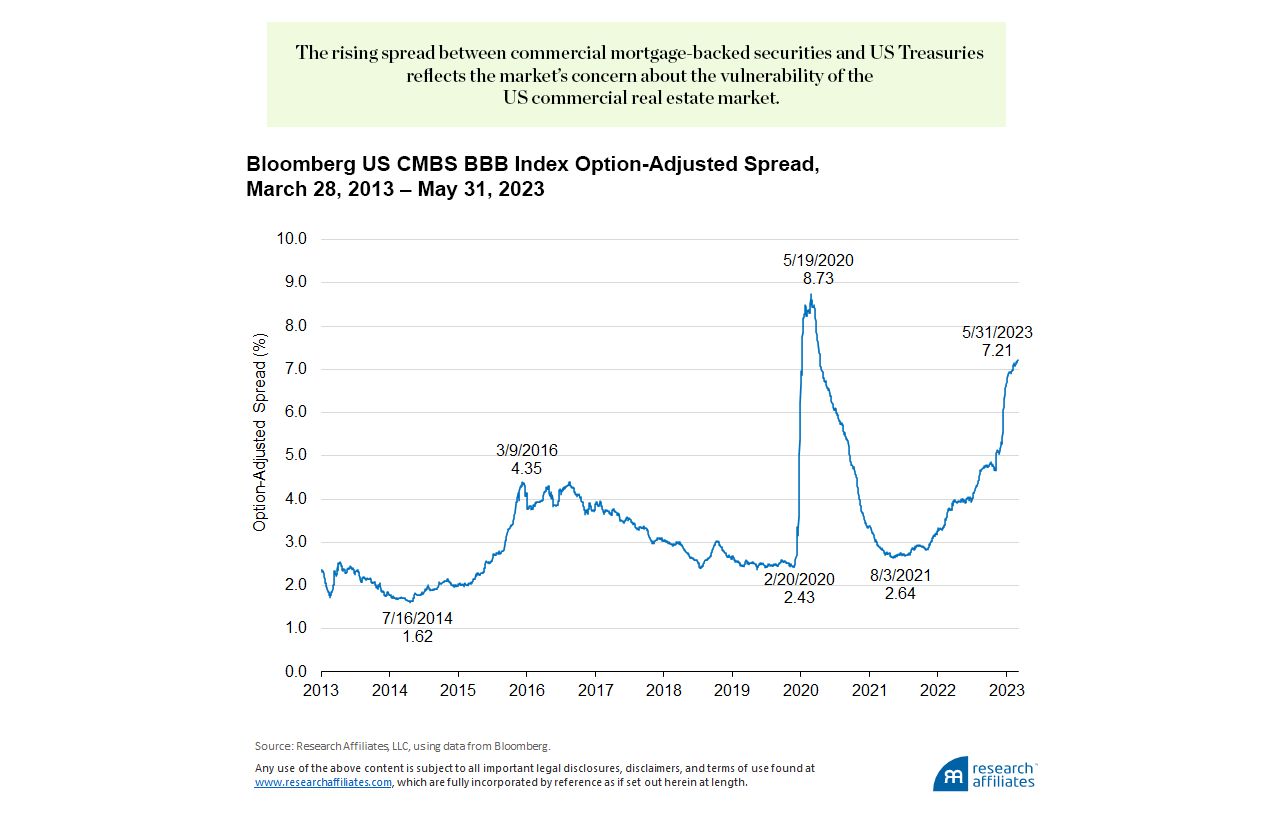

Another area of vulnerability is commercial real estate. The spread between commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) and Treasuries has been climbing for a while.

Commercial real estate is a fragile market because the demand for commercial space is so low, with few expectations it will improve anytime soon. A striking fact is that the number of New York City subway riders is down more than 50% from pre-pandemic levels. Work-from-home (WFH) mandates during the pandemic lockdowns have ushered in widespread WFH policies for one-time office workers and have lowered demand for commercial office space. I have seen this firsthand at my university, where buildings were planned to accommodate faculty and staff. Construction has been canceled in the wake of WFH. Commercial real estate could be the next source of stress in the economy.

Recession drums are beating

At this point, recession appears to be just around the corner. The question is, will it be a hard or soft landing? While no Fed hike in June is welcome news, a "pause" is not good enough. Further hikes after June will compound the risk to our financial system and further increase the probability of a dreaded — and unnecessary — hard landing.

Please read our disclosures concurrent with this publication: https://www.researchaffiliates.com/legal/disclosures#investment-adviser-disclosure-and-disclaimers.