Net Zero by 2050: Australia, Get Ready for EU-Style Climate-Investing Regs

Europe has led the way in regulation aimed at mitigating climate change. This regulation presumes climate change poses a material risk to investors and that trustees and managers have a fiduciary duty to incorporate this risk in their oversight policies and management of investment portfolios.

Australian regulators are turning their attention to ESG and “green” investment products to ensure they are true to label and are calling out the EU as an example of a legal framework that defines which investments are climate friendly. Australian advisors and investors are well advised to take note of the increasing regulatory pressure to measure and report on the sustainability activities of companies held in investment portfolios.

We summarize European regulation to help Australian investors plan how to align their investment policies, portfolio positions, and reporting practices now with the new regulatory structure for sustainable finance emerging in Europe and other developed nations.

On 26 October 2021 the Government announced Australia’s Long-Term Emissions Reduction Plan (the Plan) to reach net zero by 2050, with technology, not taxes, doing the heavy lifting. The Plan focuses on driving down the costs of carbon-free energy production and carbon-capture technologies. Achieving these technology-driven targets will require significant future investment. Without the stick of a carbon tax, the Government, most likely through its Regulators, will require investors to drive the focus on green technology. The consequence of these lofty goals is that climate transition investing is coming to Australia. It’s not a matter of if, but how quickly.

Acclimating to this new framework means investment professionals must manage climate-related investing metrics as we design and implement investment strategies for carbon-sensitive investors. Now is the time for Australian investors to plan how to align investment policies, portfolio positions, and reporting practices with the impending regulation. We outline here the relevant trends in the progression of climate-related investing regulation, a global wave soon to make its way to Australia.

Climate Regulation Going Global

Australia has been a signatory to the Paris Agreement, a legally binding international UN treaty under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, since 2006. The Paris Agreement aims to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change by holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and by pursuing efforts to limit temperature increase to 1.5°C.1 Achieving this ambitious goal requires unpreceded cooperation—both among governments and between business and government. As the impact of the looming commitments to the Paris Accord makes ripples globally, Australian investors should look to Europe’s regulatory approach as a guide to understanding this coming regulatory shift and its implications for climate transition investing.

Europe has led the regulatory effort in climate investing. European regulation presumes that climate change poses a material risk to investors and that trustees and managers have a fiduciary duty to incorporate this risk in their oversight policies and management of investment portfolios.

Until now, Australia seems to have lagged the legislative progress of the large democratic countries of Europe, the United Kingdom, and now the United States. Using his 4 July 2021 Independence Day address, the most senior consular official in Australia, American Chargé d’Affaires Mike Goldman, underlined the importance for Australia to join the group:

Looking to that future, Australia offers great potential for building resilient and secure supply chains, particularly on critical minerals and battery materials. And we have much to gain together by partnering to develop new, green technologies and by setting new, more ambitious climate goals. As partners, we have a shared obligation to protect our planet by taking the climate crisis...head on.2

A recent important development is the introduction of the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (EU-CBAM), which is to be effective from 2026. The United States, Japan, and Canada are working to implement similar mechanisms in the near future. The EU-CBAM is aimed at stopping firms from outsourcing their carbon production to less-regulated countries, effectively taxing imports for upstream carbon production at the effective price of the EU carbon market.

US President Biden is now characterising climate change as an existential threat, and his administration intends to join Europe’s regulatory effort, reversing the course of US climate policy adopted by the previous administration. The United States under President Biden has rejoined the Paris Agreement, ordered a review of Trump-era Department of Labor guidelines, and announced a non-enforcement policy of the present ESG and proxy voting rules while the review takes place.3 In February, the US House of Representatives introduced the Climate Risk Disclosure Act of 2021, which requires companies to disclose physical and transition risks associated with climate change (although passage by the US Senate seems unlikely). The Securities and Exchange Commission recently created the Climate and ESG Task Force and issued a statement requesting public comment on climate-related company disclosures to inform its policymaking.4, 5

Now is the time for Australian investors to plan how to align their investment policies, portfolio positions, and reporting practices to be consistent with impending climate-related investing regulation.

”The Australian government has a very turbulent history in carbon-related legislation. The Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme (CPRS) legislation failed to pass the Senate in 2009 and the Clean Energy Act 2011 was passed in February 2011, only to be repealed in 2014. Surprisingly, the regulator of the Clean Energy Act 2011 survived and oversees trading in a purely voluntary domestic carbon market. Perhaps with the Government’s announcement of the Plan to meet the net-zero target by 2050, the tide has turned.

While the future of Australian regulation on climate transition is politically fraught, demand for carbon-sensitive investment products has boomed. A recent report from the Responsible Investment Association Australasia (RIAA) stated:

86% of Australians expect their superannuation or other investments to be invested responsibly and ethically. These investors are not only motivated by their personal values but also, increasingly, by financial returns—62% of Australians surveyed believe ethical or responsible super funds perform better in the long term (up from only 29% in 2017) (RIAA, 2020).

In July 2021, Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) Commissioner Cathie Armour warned issuers of ESG and “green” investment products that the products need to be true to label. She cautioned that ASIC is

currently conducting a review to establish whether the practices of funds that offer these products align with their promotion of these products; in other words, whether the financial product or investment strategy is as ‘green’ or ESG-focused as claimed (Armour, 2021).

Armour also listed the EU as a jurisdiction that has adopted a legal framework that defines which investments can be considered climate friendly. Australia, we should take notice!

The Alphabet Soup of Climate Finance Regulation

European regulatory trends reveal the destination to which the United States and other developed nations, including Australia, are likely now setting their course.6 In Europe, the two principal bodies making recommendations for climate transition regulation are the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and the Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance (TEG). For those new to the alphabet soup of European financial regulatory bureaucracy, the TCFD was established in 2015 by the Financial Stability Board (FSB), an international organisation funded by the Bank for International Settlements that recommends financial regulatory standards to G20 governments. The TEG was established by the European Commission in 2018 to develop and recommend sustainable finance legislation to the European Union (EU).

TCFD. The FSB established the TCFD to “develop recommendations for more effective climate-related disclosures that could promote more informed investment, credit, and insurance underwriting decisions and, in turn, enable stakeholders to understand better the concentrations of carbon-related assets in the financial sector and the financial system’s exposures to climate-related risks.”7 The TCFD framework requires companies to disclose risks related to the transition to a low-carbon economy and risks related to the physical impact of climate change. Of companies with market capitalisations greater than US$10 billion, 42% currently disclose at least some information in line with TCFD recommendations (FSB, 2020). In November 2020, the United Kingdom announced that reporting along TCFD guidelines will be mandatory by 2025 and will apply to almost all of the nation’s economy: public companies, large private companies, banks, insurance companies, asset managers, and pension schemes.

TEG. As outlined on the European Commission’s website, the purpose of the TEG is to provide “an EU classification system—the so-called EU taxonomy—to determine whether an economic activity is environmentally sustainable; an EU Green Bond Standard; methodologies for EU climate benchmarks and disclosures for benchmarks; and guidance to improve corporate disclosure of climate-related information.”8

The EU taxonomy is a “tool to help investors, companies, and issuers and project promoters navigate the transition to a low-carbon, resilient, and resource-efficient economy” (TEG, 2020, p. 2). The taxonomy sets reporting standards and performance thresholds. Starting in January 2022, all fund providers, insurance product providers, and pension plans who market their strategies in the EU as being sustainable must report using the taxonomy framework. Financial market participants will be required to disclose how the taxonomy was used “in determining the sustainability of underlying investments, to what environmental objective(s) the investments contribute, and the proportion of underlying investments that are taxonomy aligned, expressed as a percentage of the investment, fund, or portfolio” (TEG, 2020, p. 37).

The EU Green Bond Standard (GBS) is intended to increase the “transparency and comparability of the green bond market, as well as to provide clarity to issuers on the steps to follow for an issuance, in order to scale up sustainable finance.”9 The purpose of the GBS framework and reporting requirements for proceeds of green bond issues is to increase the availability of financing, and to lower the cost of that financing, for projects aimed at reducing climate change.

Australian investors should look to Europe’s regulatory approach as a guide to understanding the coming regulatory shift and its implications for

climate-transition investing.

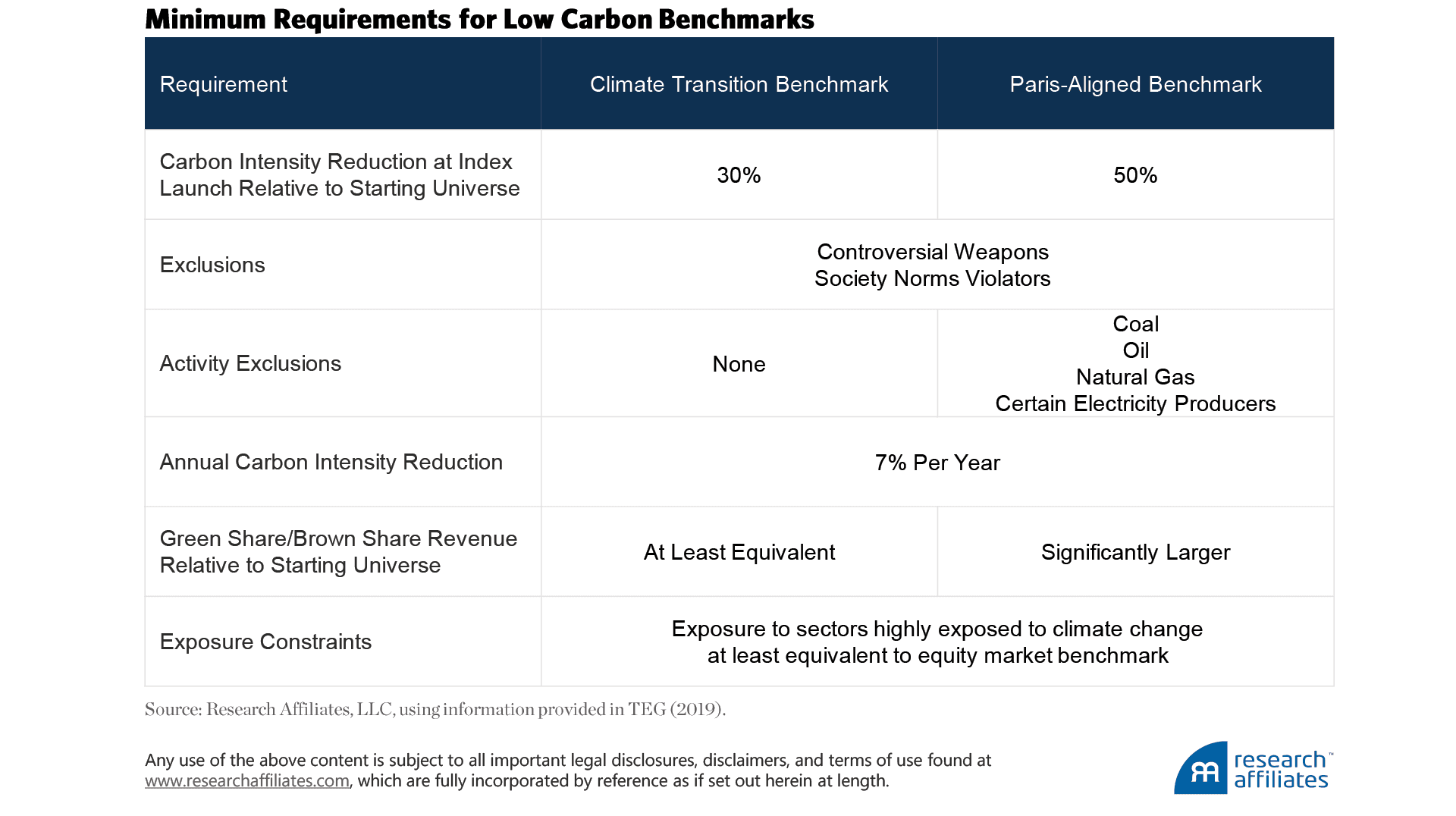

The EU Regulation for Low Carbon Benchmarks provides the “definition of minimum standards for the methodology of the ‘EU Climate Transition’ and ‘EU Paris-aligned’ benchmarks that are aligned with the objectives of the Paris Agreement and addressing the risk of greenwashing.” The TEG “has also worked on disclosure requirements in relation to Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors in the benchmark statement and the benchmark methodology for all types of benchmarks (except interest rate and foreign exchange benchmarks) including the standard format to be used to report such elements.”10

A summary of the minimum standards of the EU benchmarks is provided in the following table:

Carbon Production and the Global Listed Equity Market

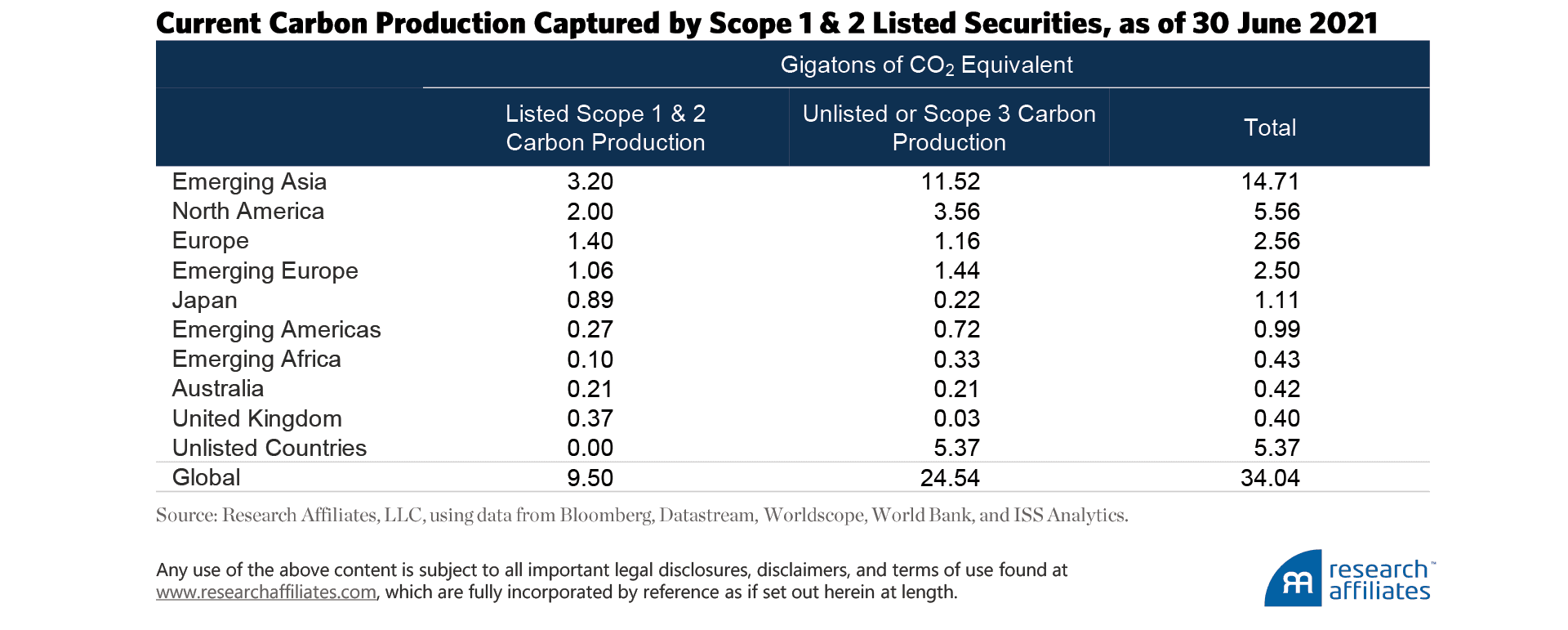

Both the UK and EU guidelines on low carbon investments seek to eliminate the carbon production of investments well before the 2050 target stated in the Paris Accord; the Paris-Aligned Benchmark aims to hit the zero-target within the current decade. The reality is in the current definition of carbon intensity, which at this time captures only scope 1 and 2 emissions. The intent is for the calculation to begin to capture scope 3 emissions in a staggered manner by industry sectors beginning in 2021 through 2025.11

Of the total 34.04 gigatons of carbon emissions generated by listed and unlisted companies around the world as of 30 June 2021, the scope 1 and 2 emissions of listed equity securities capture 9.50 gigatons,12 or 28% of the global total. Emerging Asia, encompassing two-thirds of the world’s population, generated the greatest carbon emissions, followed by North America and developed Europe.

How do we go about measuring the carbon intensity of an investment? The first step is to consider how to attribute the produced CO2 emissions (CO2e). A simple way would be to attribute all of a company’s produced CO2e to the liquid, listed equity holders. This could be done by dividing carbon produced by the free-float equity value of the company. This value could be considered the “carbon yield” at which the company is currently trading. Although appealing in its simplicity, this approach gives a free ride to the company’s bond holders and any closely held equity.

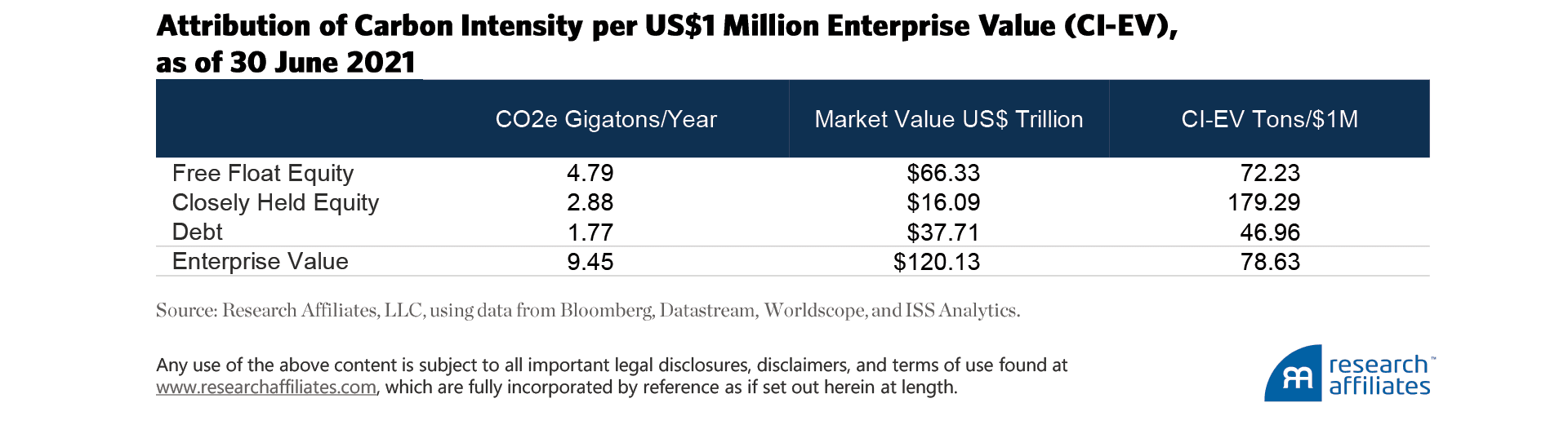

The European Union adopted a broader definition, spreading the volume of CO2e production across a company’s entire enterprise value. The burden of the company’s CO2e production is thus shared by the free-float and closely held equity holders as well as by the bond holders. Under the EU definition, the global listed market’s 9.50 gigatons of CO2e would be spread, as of 30 June 2021, across US$120 trillion of market enterprise value including cash (EVIC).13 The result is a carbon intensity per US$1m14 EV (CI-EV) of 78 t.

Carbon intensity is not the same across the three investor groups: free-float equity investors, closely held equity investors, and bond investors. Using the EU definition, let’s look at the carbon intensity of these three groups. The US$66 trillion of market capitalisation of free-float equity investors is attributed 4.8 gigatons of CO2e, yielding a carbon intensity of 72 t per US$1 million.

Companies with larger closely held equity stakes, valued at approximately US$16 trillion, have higher CO2e production; for each US$1 million of closely held equity, the CI-EV is 178 tons. The three largest contributors to the higher CI-EV for the closely held equity universe are China National Building Material Company, NTPC Limited, and Korea Electric Power Corporation.15

The third investor group, bond holders, at a market value of US$37 trillion in debt has the lowest CI-EV of 47t per US$1 million, given the large debt holdings of the low CO2e-emitting financial companies.

Certainly, the intuitiveness of the CI-EV measure is pleasing, but it can lead to counterintuitive behavior. Because the measure is based on market values, an increase in a company’s market value will lower its CI-EV without any action by the company in limiting CO2e production. Additionally, because the enterprise value of a company is based on the present value of its future business, the company could raise capital through debt, equity, or both, for a large future expansion into a carbon-intensive product line, but see a short-run fall in their CI-EV measure. Consequently, more-expensive portfolios from a value perspective tend to have a bias toward lower CI-EV measures.

The United Kingdom has gone a different direction by defining carbon intensity based on a company’s revenues (CI-Rev). Under the UK definition, CI-Rev represents a company’s produced CO2e in tons divided by the company’s revenues in millions of UK pound sterling (we use US dollars). By dividing CO2e production by revenues, each company’s carbon intensity will be comparable across time and likely across competitors in the same industry. For example, if a company doubled production in a given year, the company’s revenues should rise commensurately. The CI-Rev measure should readily reveal if the company is able to expand production and revenue in a CO2e friendly, neutral, or unfriendly way. A firm’s revenues arise from consumer spending. Therefore, we can easily weight the CI-Rev by a consumption basket to estimate our investment portfolio’s carbon footprint.

Whereas the UK revenue-based carbon measure CI-Rev does not lead to logical units for an investment portfolio, the metric does a better job of dealing with carbon production per unit of manufacture, particularly when comparing companies across the same industry. Despite their very different methods of scaling, considering all the issues we have raised in this article, these two measures of carbon intensity exhibit very similar profiles.

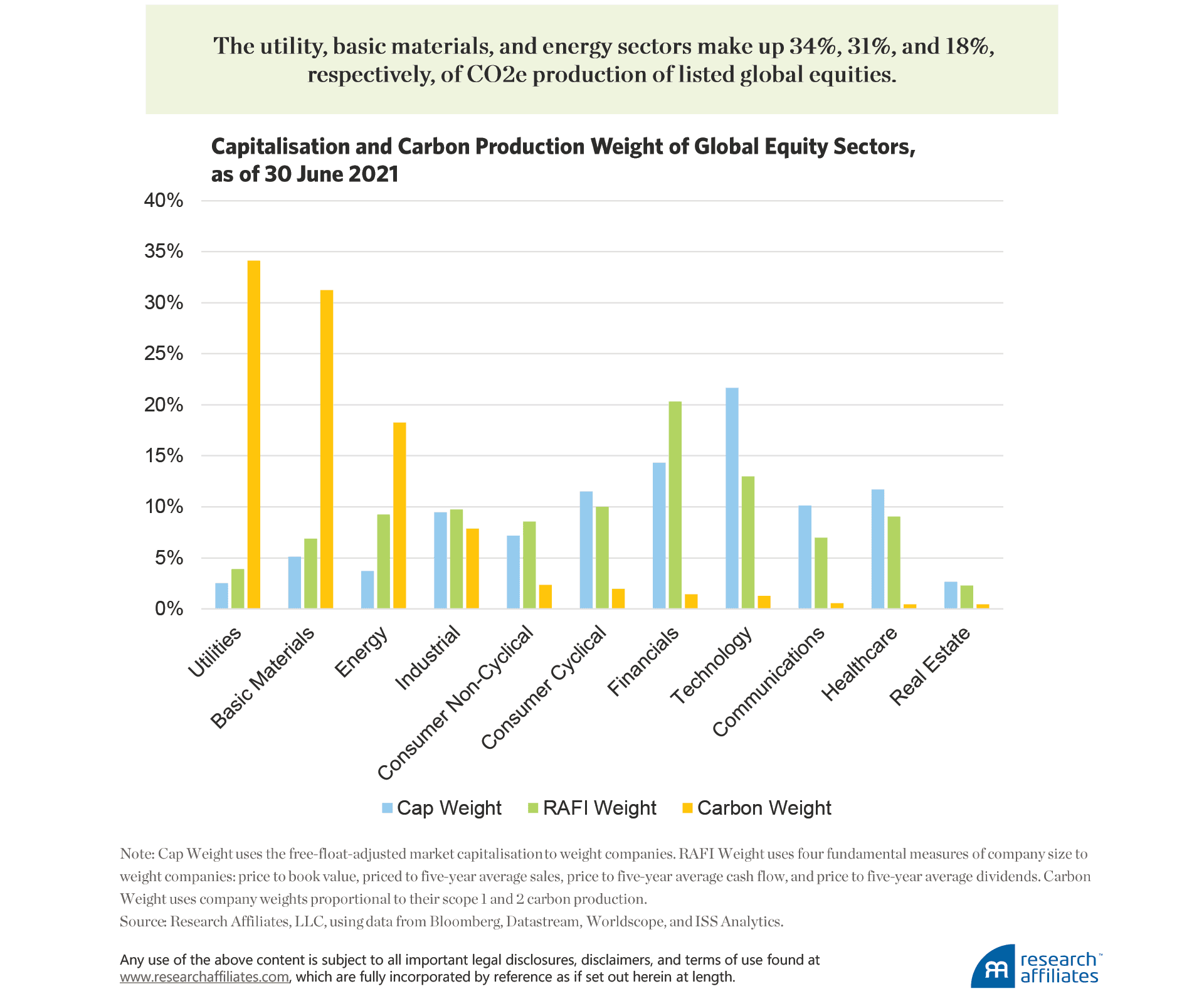

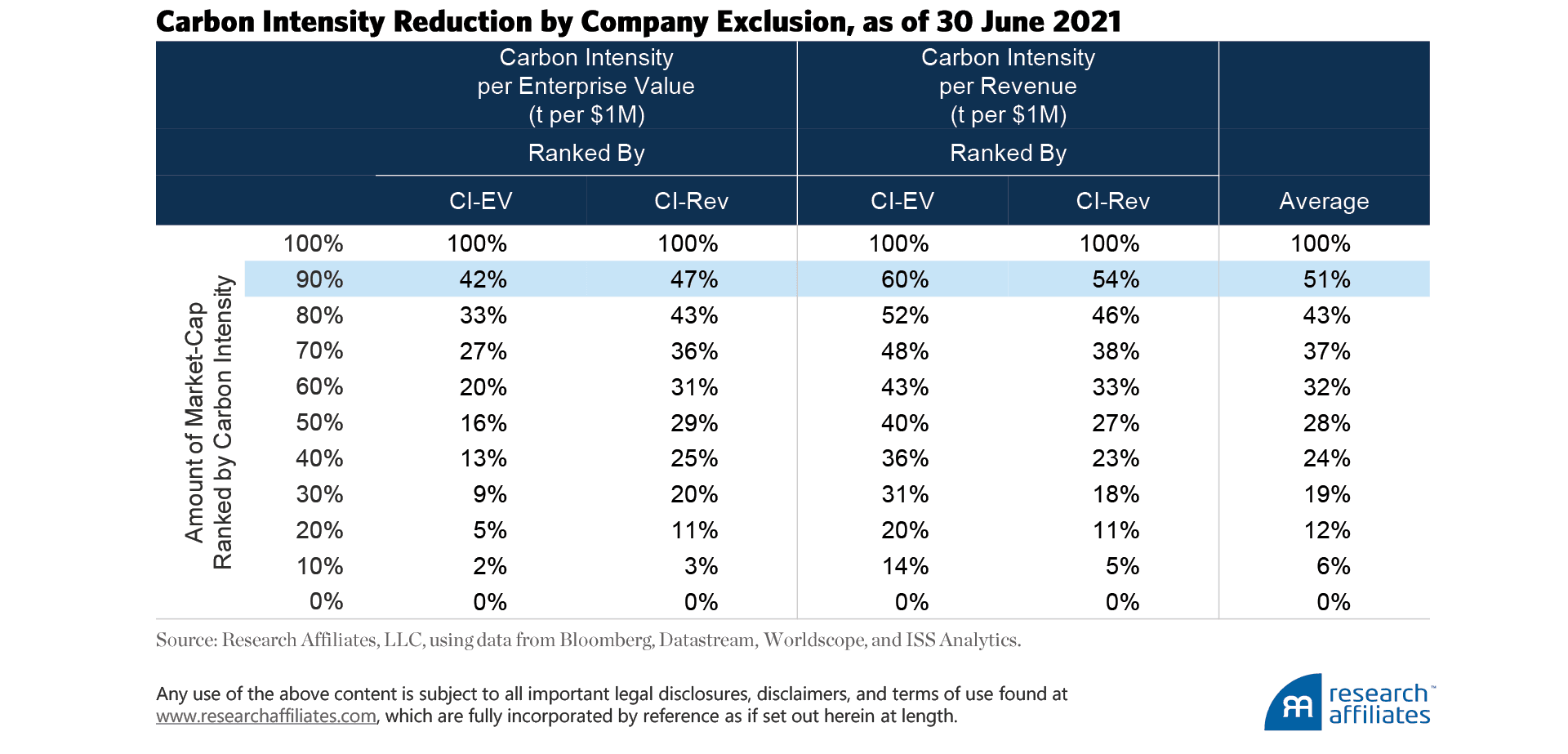

Carbon intensity varies markedly for firms across different industries. For the global free-float equity portfolio (global equities), the utility, basic materials, and energy sectors make up 34%, 31%, and 18%, respectively, of CO2e production, but only 3%, 5%, and 4%, respectively, of the global equity portfolio. If we include the industrial sector, over 90% of CO2e production represents only 20% of the assets in the global equity portfolio. Although easy to reduce a portfolio’s carbon footprint by cutting out investments in these four sectors, we have calculated a portfolio’s reduction in carbon intensity by eliminating the most carbon-intensive companies in each sector.

By removing the top 10% and leaving the lowest 90% by equity value, we can estimate the remaining portfolio’s CI-EV and CI-Rev, which falls into a range of 42% to 60% of the initial global equity carbon intensity, or 51% on average. The initial gains are substantial for such a small change in the portfolio. Further lowering the carbon intensity cutoff leads to a more-linear trade-off, roughly a reduction in each of about 10% by removing the highest carbon-intensive companies.

Initially, investing in a carbon-sensitive manner will be relatively easy, but as time passes and the carbon-intensity hurdles get higher, it will become more difficult. That said, significant progress is being made every year by companies in becoming less carbon intensive.

Conclusion

The wave of climate-transition investing regulation appears to be steadily surging toward Australia, especially in light of the Government’s stated net-zero target by 2050. The increasing regulatory pressure to measure and report on the sustainability activities of companies held in investment portfolios will necessitate that investment professionals be aware of and manage climate-related investment metrics as we design and implement investment strategies for carbon-sensitive investors. Now is a good time for Australian investors to plan how to align their investment policies, portfolio positions, and reporting practices to be consistent with Australian regulators’ focus not only on the net-zero target, but on true-to-label investing. Australian investors should anticipate similar regulation being adopted to that adopted by other developed nations.

Please read our disclosures concurrent with this publication: https://www.researchaffiliates.com/legal/disclosures#investment-adviser-disclosure-and-disclaimers.

Endnotes

- Source: https://www.industry.gov.au/policies-and-initiatives/australias-climate-change-strategies/international-climate-change-commitments

- Source: https://au.usembassy.gov/independence-day-message-from-charge-daffaires-mike-goldman/

- Source: https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ebsa/laws-and-regulations/laws/erisa/statement-on-enforcement-of-final-rules-on-esg-investments-and-proxy-voting.pdf

- Source: https://www.sec.gov/news/public-statement/lee-climate-change-disclosures

- Kalesnik, Wilkens, and Zink (2021) offer recommendations for climate-related company disclosures based on their research on corporate carbon emissions data.

- A complete review of regulations related to climate risk and ESG in general are too numerous to cover and out of scope for this paper. Fortunately, the Principles for Responsible Investment maintains a regulation database that can be found at https://www.unpri.org/policy/regulation-database. The database summarizes regulations, standards, and other ESG-related developments on a country-by-country basis.

- The stated goal of the TCFD as described on its website at https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/about/

- Source: https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/sustainable-finance-technical-expert-group_en

- Source: https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/sustainable-finance/eu-green-bond-standard_en

- Source: https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/sustainable-finance-technical-expert-group_en

- Scope 1 emissions are the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions released to the atmosphere as a direct result of an activity or series of activities at the facility level. Scope 1 emissions are sometimes referred to as direct emissions. Scope 2 emissions are the GHG emissions released to the atmosphere from the indirect consumption of an energy commodity (e.g., from the use of electricity produced by the burning of coal in another facility). Scope 2 emissions from one facility are part of the scope 1 emissions from another facility. Scope 3 emissions are the indirect GHG emissions other than scope 2 emissions that are generated in the wider economy. Scope 3 emissions occur as a consequence of the activities of a facility, but from sources not owned or controlled by that facility's business.

- Because scope 2 emissions are generated in the consumption of energy, they are captured as scope 1 emissions of other facilities. If the scope 1 facility was a listed company, the 9.50 gigatons of production from the listed equity securities does include a degree of double counting.

- EVIC is the sum of the market capitalisation of ordinary and preferred shares and the book value of total debt and noncontrolling interests without deduction of cash or cash equivalents.

- The EU rules define carbon intensity as tons per EUR1 million, but we define all intensities as per US$1 million.

- Source: Research Affiliates, LLC, using data from Worldscope.

References

Armour, Cathie. 2021. “Green Clean.” Company Director, Australian Institute of Company Directors, vol. 37, no. 6 (1 July):30.

FSB. 2020. Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures: 2020 Status Report. Financial Stability Board (October). Available at https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/P291020-1.pdf.

Kalesnik, Vitali, Marco Wilkens, and Jonas Zink. 2020. “Green Data or Greenwashing? Do Corporate Carbon Emissions Data Enable Investors to Mitigate Climate Change?” Available on SSRN.

RIAA. 2020. Responsible Investment Benchmark Report 2020: What Is Greenwashing and What Are Its Potential Threats? Responsible Investment Association Australasia.

TEG. 2019. TEG Final Report on Climate Benchmarks and Benchmarks’ ESG Disclosures. EU Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance Technical Report (September). Available at https://ec.europa.eu/.

TEG. 2020. Taxonomy: Final Report of the Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance. EU Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance Technical Report (March). Available at https://ec.europa.eu/.